Financial Conditions Make A Monetary Roundtrip and Undercut the Need for Rate Cuts

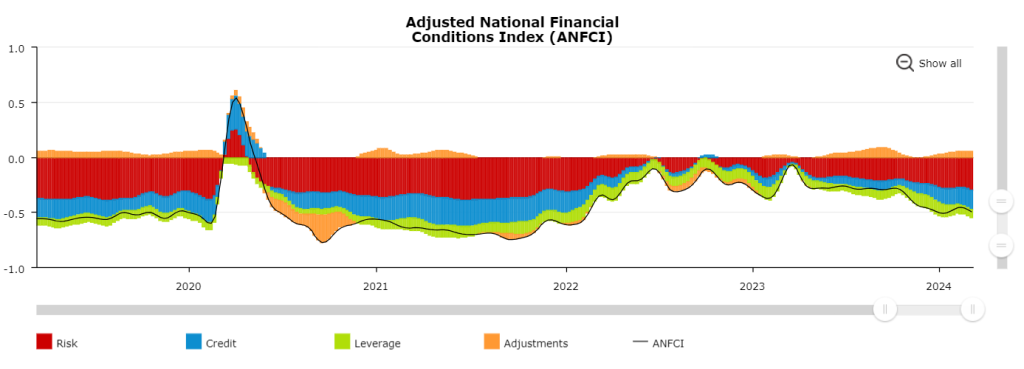

Posted: March 18, 2024 Filed under: Bond market, Central bank, commodities, CPI, Economy, gold, Jobs, Monetary Policy, oil, PPI, Stock Market | Tags: copper, CPI, Economy, FCX, Federal Reserve, finance, Freeport McMoRan, GDP, gld, gold, initial claims, interest rates, iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond ETF, Jerome Powell, lumber, National Financial Conditions Index, NFCI, oil, PPI, S&P 500, SPDR Gold Shares, SPY, TLT, unemployment, United States Oil Fund 2 CommentsLast week, financial markets stared in dismay at “sticky” inflation numbers on the consumer and wholesale side. Both the CPI (consumer price index) and wholesale inflation (the producer price index or PPI) printed slightly higher than “expected” (headline and core) and added to the sense that inflation may have gone from fizzle to sizzle. While overall momentum still favors an eventual confirmation for those who declared inflation dead last year, a more important reality looms to undercut the need for the Federal Reserve to cut interest rates. Financial conditions are just as loose as they were in the months leading up to the launch of the Fed’s aggressive campaign to tighten monetary policy (launched in March, 2022). This monetary roundtrip is evident in the Federal Reserve Board of Chicago’s National Financial Conditions Index (NFCI) (follow the black line for ANFCI):

I am tempted to say financial markets have already done the Fed’s work. However, it is very likely that the minute the Federal Reserve even hints that rate cuts could be delayed until next year, the resulting tantrum in financial markets could be epic. The Fed is loathe to disappoint markets, and the message from the last meeting and subsequently from Jerome Powell has been to promise a rate cut sooner than later. Financial markets have persistently focused on any and all dovish twinges in Fed-related pronouncements. For example, from Powell’s testimony to Congress on March 6th (emphasis mine):

“We believe that our policy rate is likely at its peak for this tightening cycle. If the economy evolves broadly as expected, it will likely be appropriate to begin dialing back policy restraint at some point this year. But the economic outlook is uncertain, and ongoing progress toward our 2 percent inflation objective is not assured. Reducing policy restraint too soon or too much could result in a reversal of progress we have seen in inflation and ultimately require even tighter policy to get inflation back to 2 percent. At the same time, reducing policy restraint too late or too little could unduly weaken economic activity and employment.”

Powell can insert all the standard caveats he wants. Markets read this statement as saying rate cuts are on their way!

A Nervous Bond Market

Yet, bond markets have been a little “nervous” all year. For example, the iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond ETF (TLT) has trended downward (meaning higher bond yields) so far this year with lower highs and lower lows. From TradingView:

TLT is just a fresh low of the year away from finally catching the stock market’s attention again.

Copper, Lumber, and Oil – oh my!

The bond market has good reason for some jitters. Several commodities have sprung back to life this year. Copper miner Freeport-McMoRan Inc (FCX) is welcoming the upcoming Fed meeting with a 7+ month high. FCX is up 19.8% in less than two weeks. (FCX has been stuck in a trading range since the beginning of 2021).

Lumber bottomed out in early 2023. This month, lumber broke out above last summer’s high and is back to levels last seen in August, 2022.

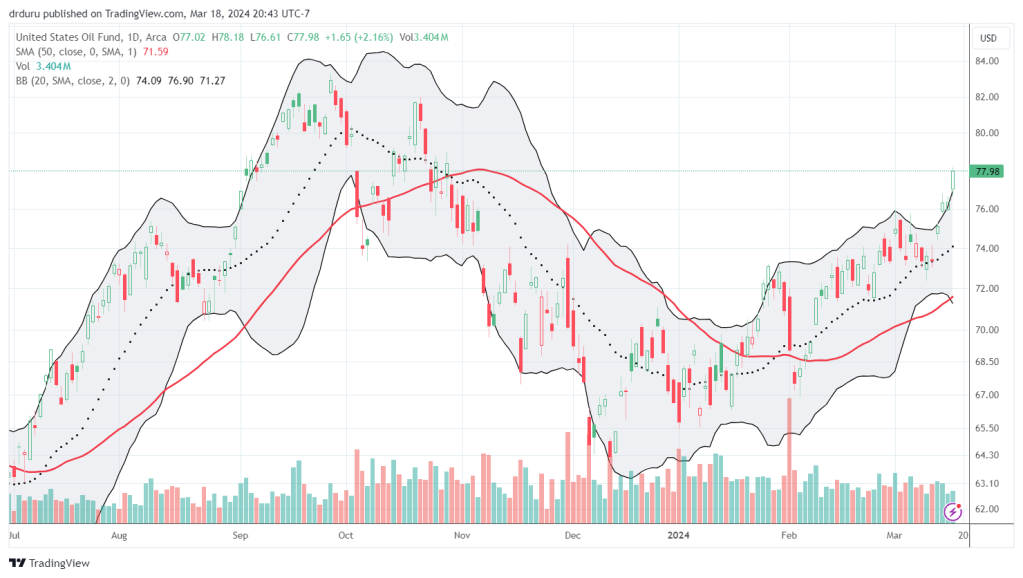

Oil, everyone’s favorite non-core component of inflation, has been in “stealth” rally mode all year. The United States Oil Fund, LP (USO) looks ready to launch parabolically on the wings of rate cuts.

Where will these prices go with rate cuts? I vote higher.

The Golden Touch

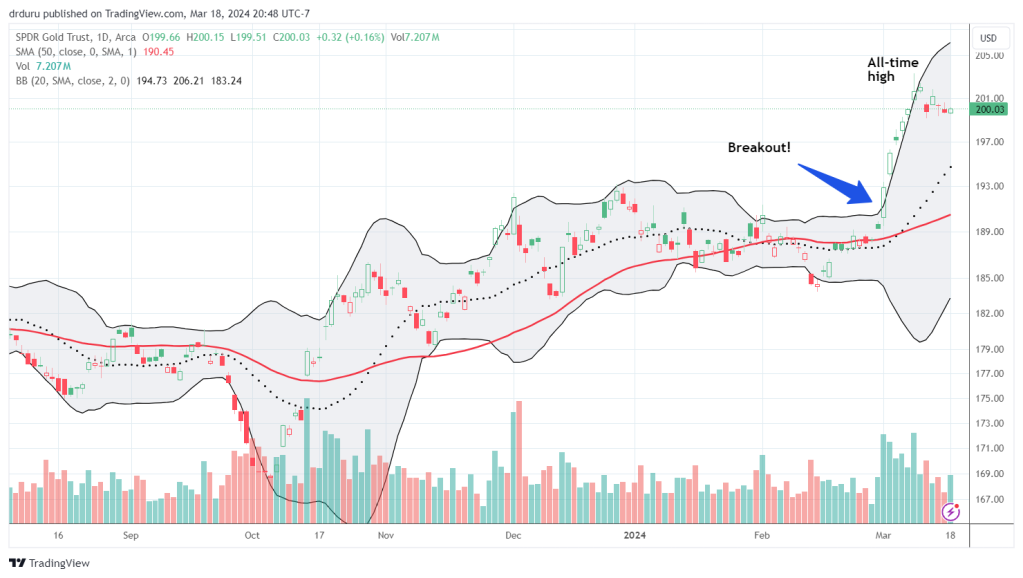

Speaking of getting ready for rate cuts, gold, my favorite hedge enjoyed a spectacular (and overdue) breakout this month. SPDR Gold Shares (GLD) traded at an all-time high at its peak this month.

I like buying the dips in GLD going forward. The odds seem sufficiently high for the Fed to feel “forced” into easing into a sea of market liquidity.

Straining to See the Weakness in Labor Markets

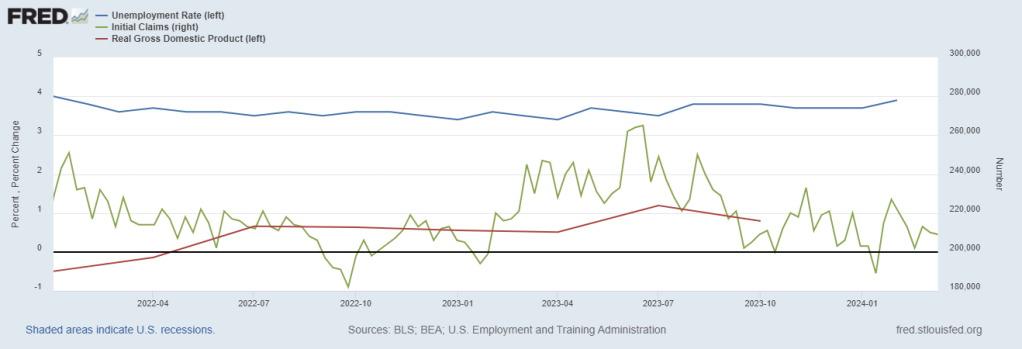

So maybe the Fed can strain its economic gaze and find an excuse to do a “proactive” rate cut. The graph below shows the unemployment rate has likely bottomed out (left axis and blue line) Yet, it remains near historic lows. Initial unemployment claims have been trendless with a recent peak set last summer (right axis and green line). Finally, real GDP quarter-over-quarter growth has levitated in positive territory and for the last two years has defied overly persistent expectations for a recession (right axis and red line). From my perch, I see no excuse for a rate cut here, but perhaps I am not creative enough with the data.

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Unemployment Rate [UNRATE], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; U.S. Employment and Training Administration, Initial Claims [ICSA], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Real Gross Domestic Product [GDPC1], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

The Stock Market’s Giddy Anticipation

The stock market’s giddy anticipation of rate cuts is poetic. The stock market has soared on loosening financial conditions and has been able to ignore just about any bad news the macro environment tries to toss out there. Recent successive all-time highs speak volumes to the buffer the Fed can enjoy if it so chooses to wait out the Presidential election before making changes to monetary policy.

Conclusion

With market breadth increasingly lagging the stock market’s ascension, I have been a skeptic about the overall rally for several weeks. The Federal Reserve is probably the last catalyst between now and the Presidential election that has a chance of validating my skepticism. If the Fed complies with the market’s giddiness, there is no telling how high the market could soar in coming months. If the Fed decides to wait things out, the stock market will lose a major contributor to the upward and higher fund. Then again, maybe the Fed pulls off a magical “hawkish rate cut” (one and done rate cut with a warning about the potential for inflation to rise from the ashes). The Fed could figure out just the right balance between disappointing the stock market and fueling ever increasing levels of speculation and higher commodity prices…

Be careful out there!

Full disclosure: long GLD

From Inflation Fizzle to Sizzle

Posted: February 13, 2024 Filed under: Bond market, CPI, Currencies, Housing, Monetary Policy | Tags: Canadian dollar, CME FedWatch Tool, Consumer Price Index, CPI, DXY, Economy, EUR/USD, Federal Reserve, finance, FXC, FXE, inflation, Invesco CurrencyShares Canadian Dollar Trust, Invesco CurrencyShares Euro Currency Trust, iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond ETF, Monetary Policy, NAHB, National Association of Home Builders, rate probabilities, services inflation, shelter inflation, TLT, U.S Dollar, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, USD/CAD, VIX, volatility index 1 CommentInflation is probably still dead, but its “stickiness” still has the potential to spook financial markets. In the middle of a giddy dance on inflation’s grave celebrating an inflation fizzle, the January, 2024 CPI (consumer price index) report delivered sizzle with a hotter than consensus expectations and sent the bond and stock market into a swirl. The following table comes from a CNBC interview with National Economic Director and former Federal Reserve vice chair Lael Brainard:

Nevermind that a read hotter than consensus has little impact on the current trend. The chart below from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that even as core CPI (all items less food and energy) is flattening out a bit (the red line), the “sticky” shelter component of inflation is still hurtling downward (the purple line).

With the trend still favoring the death of inflation, I think of “sticky” as a reference to people’s impatience with an inflation component taking too long to converge with the overall average inflation level. The CPI report highlighted the relative stubbornness of shelter inflation:

“The shelter index increased 0.6 percent in January, and was the largest factor in the monthly increase in the index for all items less food and energy. The index for owners’ equivalent rent rose 0.6 percent over the month, while the index for rent increased 0.4 percent. The lodging away from home index increased 1.8 percent in January…The shelter index increased 6.0 percent over the last year, accounting for over two thirds of the total 12-month increase in the all items less food and energy index.”

The bubble chart below from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics shows the outsized influence of services less energy services on total inflation (the large purple bubble). This major component includes shelter. Its relative importance of 60.9 dwarfs the relative importance of all other major components of inflation.

Given the angst directed at the shelter component of inflation, I looked at what the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) had to say about this CPI report. The industry group provided a reassuring conclusion: “the NAHB forecast expects to see shelter costs decline further in the coming months. This is supported by real-time data from private data providers that indicate a cooling in rent growth.” So while the housing price picture is mixed with existing homes on the uptick and new homes on the downtick, overall rents should continue a cooling pace as expected.

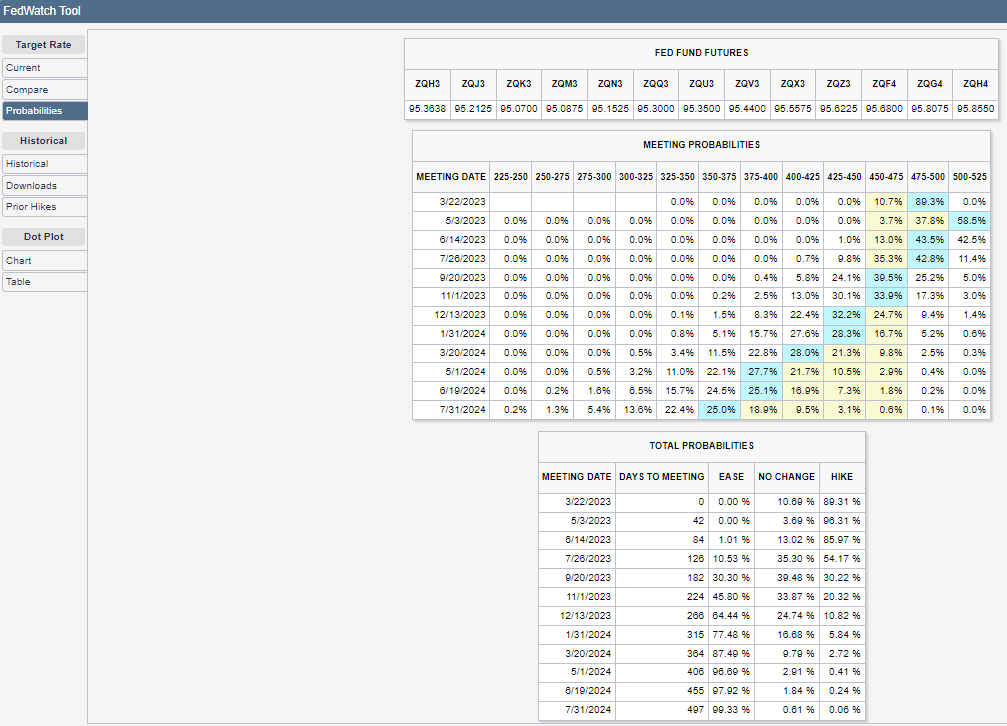

Unfortunately for those traders and investors buying stocks and bonds in anticipation of rate cuts, this reminder of inflation’s stickiness pushed out expectations for the first rate cut from the Federal Reserve. Over-eager financial markets pushed out the first rate cut from May to June. This is a bitter pill to swallow for those who started buying stocks and bonds late last year in anticipation of a rate cut in March (because the Fed admitted to inflation’s death of course). The chart from the CME FedWatch Tool shows how the odds favoring a May rate cut immediately evaporated.

The Fizzle and Sizzle in Financial Markets

Interestingly, currency markets and the bond market have been moving counter to the rallies in the S&P 500 (SPY) and the NASDAQ (COMPX). The 2024 rally in the U.S. dollar index (DXY) has taken the index ABOVE the point where currency traders dumped the dollar in the wake of inflation’s death. The chart below from Tradingview.com shows a bullish breakout for the dollar last month above its 50-day moving average (DMA) (the red line) and a successful test of the trend line as support earlier this month.

The dollar’s rally complicates my bullish trades on the Canadian dollar but also provides my latest opportunity to fade USD/CAD (Invesco CurrencyShares Canadian Dollar Trust (FXC)) within the trading range. I am net long the U.S. dollar by being short EUR/USD (Invesco CurrencyShares Euro Currency Trust (FXE)).

Excluding a sharp countertrend rally at the end of January, iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond ETF (TLT) has sold off most of 2024.

These trends further reinforce the notion and fear that perhaps earlier rate cut expectations were indeed premature. After the market’s pullback (the S&P 500 lost 1.4% and remains in an uptrend) will stocks also concede the point or will they return to ignoring deteriorating market breadth and other signs of caution in the stock market?

The volatility index (VIX) may have already blown off enough steam to soothe the groans of the bulls…for now. Note carefully how the VIX stopped going down this year and thus has an ever so slight uptrend going…

Be careful out there!

Full disclosure: net long U.S. dollar

Bank of Canada’s Macklem: The End is In Sight But Rates Are Not Returning to Pre-Pandemic Levels

Posted: January 7, 2024 Filed under: Canada, Economy, Monetary Policy | Tags: Bank of Canada, Canadian dollar, economics, Economy, FXC, interest rate, interest rates, Invesco CurrencyShares Canadian Dollar Trust, Monetary Policy, soft landing, Tiff Macklem, USD/CAD 1 CommentIn a BNN Bloomberg video interview late last month, the Bank of Canada’s governor Tiff Macklem essentially laid out the gameplan for Canada’s monetary policy in 2024. Macklem reassured Canadians that the end of inflationary pressures and tight monetary policy is “in sight.” However, he also prepared Canadians to expect a new regime of higher interest rates than was the norm before the pandemic: “I think it is reasonable to expect that they’ll come down, but they probably won’t come down to pre-crisis levels. We had 10-12 years of unusually low interest rates post Global Financial Crisis. I think there are good reasons to believe that we’re not going back to those very low rates.”

This admonition is unsurprising given Macklem’s general reluctance to declare victory over inflation. While the Bank of Canada increasingly sees the elements needed to get inflation back down to 2%, Macklem stated that “we are not there yet.” They need to see sustained and further (for “a number of months”) downward momentum in core inflation.

Cautious About the Signs of Victory Over Inflation

December’s statement on monetary policy also reflected the Bank of Canada’s wavering. The statement estimated that “data and indicators for the fourth quarter suggest the economy is no longer in excess demand. The slowdown in the economy is reducing inflationary pressures in a broadening range of goods and services prices.” These conditions should have generated a declarative victory statement. Instead, the Bank of Canada proceeded to posture staunchly against inflation: “Governing Council is still concerned about risks to the outlook for inflation and remains prepared to raise the policy rate further if needed. Governing Council wants to see further and sustained easing in core inflation, and continues to focus on the balance between demand and supply in the economy, inflation expectations, wage growth, and corporate pricing behaviour.”

Still, in the interview, Macklem acknowledged that rates are likely to start coming down in 2024. He just refused to provide a timetable.

The Soft Landing

The interviewer pointed out that the scenario Macklem portrays sounds like a “soft landing” for the economy. Macklem was careful not to use that term. Instead he pointed out that much of the adjustment in the labor market has come through a reduction in vacancies instead of a large rise in unemployment. An anticipated weakness in growth for the next 2 to 3 quarters should not generate a “deep” recession. Macklem directly claimed that “we can get inflation back to 2% without a recession.”

This year will be a transition year. By the end of the year, the economy should be in soft landing mode if all goes well.

The Canadian Dollar

The Bank of Canada released its December statement on monetary policy just as the U.S. dollar was experiencing a slight relief rally against the Canadian dollar (USD/CAD) (or the Invesco CurrencyShares Canadian Dollar Trust (FXC)). The slide resumed with the Federal Reserve’s decision on monetary policy the following week and the resulting celebration over the implicit announcement that inflation in the U.S. is dead. I had long anticipated the decline at the time with a target of testing the lower part of a trading range in place since September, 2022.

After taking profits, I am back to accumulating a short position. I expect the Bank of Canada’s on-going caution and the Bank’s refusal to get dovish to act as a tailwind for the Canadian dollar. The chart below from TradingView.com shows volatility in USD/CAD distinctly driven by key events. The Bank of Canada’s next Monetary Policy Report will come on January 24th. The Fed comes around the week after.

So, overall, I continue to favor playing the trading range in USD/CAD as an eventual trip to or toward the bottom of the range. I currently cannot foresee catalysts that will push the currency pair to stray too far away from the range. If USD/CAD escapes the range, I think the odds favor a breakdown over a breakout.

Be careful out there!

Full disclosure: short USD/CAD

Inflation Now, Inflation 76 Years Ago

Posted: January 7, 2024 Filed under: CPI, Economy, Europe, Housing, Industrial, Monetary Policy | Tags: CPI, employment, geopolitics, GI Bill, industrial policy, labor strike, labor unrest, NY Times, voter opinion, wages, World War 2, World War II Leave a commentIn “Want to Understand 2024? Look at 1948“, the New York Times drew some fascinating parallels between today’s economic and political climate and the era leading to Harry Truman’s surprise victory over Thomas Dewey in the 1948 Presidential election. One key quote summarized the context: “in the era of modern economic data, Harry Truman was the only president besides Joe Biden to oversee an economy with inflation more than 7% while unemployment stayed under 4% and GDP growth kept climbing.” I took particular interest in the references to the inflationary dynamics from around 76 years ago.

Inflation landed around 20% in 1947 according to the NY Times who also claimed it was the worst inflation America experienced over the past 100 years. The article did not specify the inflation measure, so for the purposes of discussion I assume the article referred to the entire Consumer Price Index (CPI). If so, then the 20% figure must have been for a particular month in 1947. The annual inflation for 1947 was 8.8% according to Investopedia, far short of the highest level over the past 100 years. Inflation the year before soared to 18.1% from 1945’s 2.2%. While it looks like the NYT selectively picked an inflation number for effect, it is clear that sentiment on inflation during this time was as dour as one should expect during a period of exceptionally high inflation. The following bullets are mostly direct quotes from the article reordered chronologically:

- In December 1947, more than 70% of adults said they would want their own wages to decline in order to bring prices down.

- In polling throughout 1947 and 1948, a majority supported reinstating wartime rationing and price controls.

- Before the conventions, voters said a plan to address high prices was the No. 1 priority they wanted in a party platform. More voters said they wanted prices to be addressed over the next four years than any other issue.

- In June, 1948, a majority of voters expected prices would be higher in six months (at election time in November, only 18% of voters expected the same).

- As late as summer 1948…adults expected prices to keep rising.

A combination of economic pressures sent inflation soaring.

Post-war supply shortages combined with the end of price controls to light a fire under inflation. The NY Times article pointed out that labor unrest following World War 2 exacerbated supply shortages. For example, the National WWII Museum in New Orleans observes: “With the end of the wartime no-strike pledge, workers across America expressed their frustration with wages and working conditions through a series of strikes that involved over 5 million people from the end of 1945 and into 1946.” Strikes hit broad swaths of the economy: mills, telephone service, meat packing, and General Electric (a major industrial employer at the time). The railroad strike of 1946 crippled large parts of the economy (the interstate highway system did not start until Eisenhower’s presidency in the 1950s). No doubt all this economic disruption helped dampen the national mood alongside the resulting price pressures.

Layer on pent-up consumer demand and the economy got hit with a perfect inflationary storm. Benefits from the GI Bill, not mentioned in the NY Times article, helped to stoke consumer demand. For example, while the country built very little housing during World War II, the GI Bill offered returning soldiers low interest, zero down payment home loans with better terms for newly built housing. Although Black servicemen were often denied benefits of the GI Bill (and thus they were often left in poverty), such incentives must have contributed to increased pricing pressures in the economy.

The NY Times article also did not consider the potential price distortion from large amounts of U.S. resources funneled into the Marshall Plan. The Marshall Plan kicked off in 1948, and it is plausible suppliers felt emboldened to increase prices in anticipation of the largess. Supply responses in Europe would eventually erode this pricing power.

Fast forward to today and we find parallel economic distortions putting pressure on prices. Massive fiscal and monetary stimulus stoked demand, especially for housing and related goods. Government supported pandemic savings have apparently supported on-going strength in retail spending. Wage growth has also supported robust consumer demand. While today’s labor unrest pales in comparison to post-war labor actions, the scales have tipped in favor of labor for now. Unemployment remains at historic lows, and employers have readily absorbed the rebound in the labor force participation rate. U.S. industrial policy could apply its own upward pressures on prices in the economy.

The Federal Reserve on the Sidelines of Late 1940s Inflation

The volatile cocktail of inflationary pressures must have complicated monetary policy. Compared to today’s tornadic monetary policy response, the Fed’s rate hikes in the immediate post-war years look exceptionally timid. The Federal Reserve essentially sat on the sidelines as the economy convulsed through its inflationary pressures. From “A New Daily Federal Funds Rate Series and History of the Federal Funds Market, 1928-1954“:

Today’s deflationists would have been particularly happy with the timid Fed of the late 1940s and early 1950s! Fresh memories of the economic devastation of the Depression no doubt also slowed the hand of the Fed. The NY Times article did not delve into the role of the Fed in allowing inflation to take its course in the post war years.

Inflation Today

Pandemic disruptions are mostly in repair, but Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has caused its own supply disruptions. The Israel-Hamas war threatens to cause disruptions in global oil markets and shipping lanes in the Gulf. Growing tensions between China and Taiwan and increasing authoritarian control over the Chinese economy have motivated companies to leave China in search of “safer” countries for production. This transition will likely pressures prices through increased production costs and the short-term transition costs.

In other words, while financial markets celebrate the end of the Federal Reserve’s fight against inflation, there are plenty of looming inflation risks, any of which could deliver setbacks to current trends. Seventy-six years ago inflation came to a boil and then yielded through the 1950s and early 1960s. A parallel peak for today’s inflationary era would be welcome news!

A Memorial to Inflation…The Song and the Singer

Posted: January 2, 2024 Filed under: Entertainment | Tags: Earnest Jackson, music, obituary, Planet Money, recording industry, Sugar Daddy and the Gumbo Roux 2 CommentsOn December 13, 2023, I claimed that the Federal Reserve officially declared the death of inflation. I did not know it at the time but inflation had also just died in the world of entertainment. Earnest “The Voice” Jackson, Jr. passed away a week earlier on December 6th. Jackson came to public fame after NPR’s Planet Money discovered his 1975 song “Inflation”. Some unnamed person sent Planet Money the song on a cassette tape. They naturally loved the song and decided to release it as part of a 3-part series and economics lesson that demonstrated what it takes to make a hit in the music industry. That mystery tape changed Jackson’s life just in time.

Planet Money released the song in November, 2022 under their newly formed Planet Money Records label. They had to track down all the members of the band who performed the song, Sugar Daddy and the Gumbo Roux (including Randy Jackson of American Idol fame!), and convince them to agree to terms. Planet Money even promoted the song and as of December, 2023 achieved over 2 million streams. I was one of many fans who streamed the song often and regularly to help the cause.

It is ironic Jackson died just as economic inflation (apparently) died. It is doubly ironic that Jackson passed away so soon after he finally realized his lifelong dream to get signed and hear his own song on the radio. I never got around to figuring out how to make “Inflation” a theme song for this site. Instead, I have written this small acknowledgement and memorial to Jackson for giving so many “Inflation” as a form of edutainment. I also extend a HUGE thank you to Planet Money for making the adventure happen, especially given it was a money-losing enterprise for them. The person who sent that tape must have known something…!

Earnest Jackson, Jr. died at the age of 75.

{Note: On January 2, 2024, I submitted a Wikipedia entry for Earnest Jackson. I hope to get it approved for publishing within the next month or so. It will be my first ever Wikipedia entry.}

The Federal Reserve Makes It Official: Inflation Is Dead

Posted: December 13, 2023 Filed under: Economy, Monetary Policy | Tags: DXY, Economy, Fed Fund Futures, Federal Reserve, inflation, interest rates, Jerome Powell, Monetary Policy, U.S. dollar 8 CommentsAt the risk of making Inflation Watch a lot less relevant and topical, I am pointing out that today’s meeting of the Federal Reserve essentially spoke of a victory over inflation. The threat of inflation has been vanquished; inflation is dead. In place of hawkishness and monetary tightening now comes “consideration of a time for cutting rates.” Fed Chair Powell wrestled with this concept throughout the press conference.

The key trigger word was “any.” The first question from the press zoomed directly on the insertion of “any” in the following section of the Fed’s policy statement (emphasis mine):

“In determining the extent of any additional policy firming that may be appropriate to return inflation to 2 percent over time, the Committee will take into account the cumulative tightening of monetary policy, the lags with which monetary policy affects economic activity and inflation, and economic and financial developments.”

Powell’s response essentially confirmed that the Fed thinks it is done fighting inflation with rate hikes. The Fed is so confident that it is now considering how to conduct a rate easing cycle.

“We added the word ‘any’ as an acknowledgement that we believe that we are likely at or near the peak rate for this cycle. Participants didn’t write down additional hikes that we believe are likely…but participants didn’t want to take the possibility of further hikes off the table.”

The last part about keeping rate hikes on the table is just obligatory caution that in name keeps the Fed’s options open just in case.

The next question came from Governor Chris Waller’s claim that the Fed could be cutting rates in the next several months if inflation continued to fall. Powell of course did not respond directly to the commentary, but he affirmed that the Fed has its mind on rate cuts for 2024:

“…the other question of when will it become appropriate to begin dialing back the amount of policy restraint in place that begins to come into view and is clearly a topic of discussion out in the world and and also a discussion for us at our meeting today.”

Note Powell conditioned his remarks to say that “no one is declaring victory, that would be premature.” But again, this is obligatory caution. Victory is practically oozing out of every pore of this meeting. The Fed has to take small and methodical steps in its march to victory.

Inflation Is Dead

Powell’s most revealing answer came to a question about what motivates the Fed to consider rate cuts:

“Both headline and core [inflation] have come down really significantly in three months, that’s a big piece of this. At the same time growth has turned out to be very strong in the third quarter is slowing we believe as appropriate, and we’ve got we’ve had several labor market reports which suggest again significant progress toward greater balance across a very a broad range of indicators. You’re seeing so many of the indicators come back to normal.”

Importantly, Powell noted later in the Q&A that the Fed has seen progress in the most worrisome component of the inflation basket: non-housing services. Now, all three components of core inflation are contributing to inflation’s demise.

Powell further stated that a rate hike is no longer the base case unlike 60 or 90 days ago. He pointed to individual board members who have assessments about the timing for reducing tight policy when saying “that is a discussion we’ll be having going forward.”

Notably, while Powell insisted the job remains to get inflation down to 2%, he acknowledged in response to a reminder about statements in July that the Fed cannot wait until 2% inflation to start cutting rates:

“The reason you wouldn’t wait to get the 2% to cut rates is that policy would be it would be too late. You’d want to be reducing restriction on the economy well before 2% so you don’t overshoot…you know it takes a while for policy to get into the economy and affect inflation.”

Financial Markets Are Ready for Rate Cuts Sooner Than Later

At one point recently, financial markets pessimistically rolled back the first rate cut to September, 2024. Going into this meeting, the market planted the flag on a March rate cut but retreated the day before in the wake of November CPI data. At the time of writing, the first rate cut is firmly rooted in March (source: CME FedWatch) – follow the blue colored boxes for the most likely scenario for a given interest rate policy (labeled across the top of the chart) and a given meeting date (labelled across the left side of the chart).

The comparison chart below shows how the odds for a March rate cut were 39.7% yesterday but 54% a week ago. A month ago the odds were a mere 10.5%. Market opinion has changed rapidly!

Conclusion

In the end, Inflation Watch will stay on the case. The situation remains uncertain and the citizenry are still not happy about prices. Powell admitted as much:

“The price level is not coming down…so people are still living with high prices and that’s something people don’t like. Real wages are now positive so that wages are now moving up more than inflation. As inflation comes down that might help improve the mood of people.”

So while the Fed keeps working, and wages keep trying to outpace inflation, Inflation Watch will keep on watching and reporting!

In the meantime, see below the dramatic impact of the Fed’s declaration of victory on the U.S. dollar (DXY); the recent downtrend looks ready to resume (source: TradingVIew.com).

Full disclosure: long and short U.S. currency pairs

Despite the Inflation Celebrations, the Case Against Team Transitory Still Stands

Posted: November 15, 2023 Filed under: Automobiles, Banks, Economy, Housing, Monetary Policy | Tags: auto loans, automobiles, CPI, Federal Reserve, FICO, housing market, inflation expectations, interest rates, Joseph Stiglitz, Monetary Policy, PCE, Personal Consumption Expenditures Leave a commentThe excitement over a slightly softer than “expected” October inflation print extended from financial markets – where stocks soared, the U.S. dollar plunged, and bond prices soared – to economists celebrating predictions that inflation would one day come down from lofty levels…no matter what the Fed did. In a piece published before the October CPI report, economist Joseph Stiglitz triumphantly wrote a piece titled “Turns out that inflation really was transitory, no thanks to the Fed.” Stiglitz effectively claimed that the Federal Reserve should have stuck with its transitory narrative on inflation in the immediate wake of the pandemic. This claim runs directly counter to those of us who believe the Fed rested on its transitory laurels too long and moved too slowly to start normalizing interest rates. I specifically take issue with Stiglitz’s omission of important context surrounding the Fed’s belated decision to start hiking rates:

- The Federal Reserve had driven monetary policy to historic heights of accommodation: a 9 trillion dollar balance sheet combined with a return to zero interest rates: an easy money paradigm that itself needed to be transitory.

- The Federal Reserve instituted a risk management framework that targeted tail risks instead of an “expected” path of inflation and its resulting impact on the economy.

Moreover, Stiglitz offered two examples from the economy, autos and shelter, that do not conclusively demonstrate the Fed had no impact on inflation. Even Stiglitz’s discourse on inflation expectations is open to varying interpretations. I will tackle each of these issues one-by-one starting with auto inflation.

Auto Inflation: A Counterfactual

Stiglitz makes a big deal out of the obvious fact that the Fed could not solve chip supply problems in the auto industry by hiking interest rates. While the Fed never staked a claim to such powers, and even acknowledge its lack of such powers, this complaint is common among Fed critics who apparently wanted the Fed to leave monetary policy accommodative and lower for longer. Stiglitz pulls the rug from under the Fed by insisting “Given that its interest-rate hikes did not help resolve the chip shortages, it cannot take any credit for the disinflation in car prices.”

So now with auto prices inevitably lower, critics like Stiglitz are declaring victory on the prediction that car prices would eventually come down. Fine. How about a counterfactual? If the Fed had left rates lower for longer is it credible to believe that the path for prices would have stayed exactly the same (or improve)? I claim the answer is no. Assuming lower loan rates encourage and incentivize more borrowing (indeed this is a fundamental premise for accommodative monetary policy), then rock bottom rates would have fueled on-going and even increasing demand for cars and deepened pressures against short supply. In other words, I am claiming auto inflation would have been even worse and could have caused other cascading problems in the economy.

Even throwing away abstract counterfactual arguments, the actual data is not conclusive enough to suggest the Fed had zero (or even little) impact. The chart below juxtaposes new and used car prices with the auto inventory/sales ratio (cars and light trucks). This ratio puts demand and supply into context. While the the ratio bottomed out in late 2021, it is still nowhere close to pre-pandemic levels. Deflation/disinflation should not be this dramatic with the inventory/sales ratio still at historically low levels. I would have expected a price plunge to accompany a much faster recovery in the inventory/sales ratio. In fact, I would have expected the pendulum to at least swing above 1 again.

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: Used Cars and Trucks in U.S. City Average [CUSR0000SETA02], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, November 14, 2023. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: New Vehicles in U.S. City Average [CUUR0000SETA01], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, November 14, 2023. U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Auto Inventory/Sales Ratio [AISRSA], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, November 14, 2023.

In other words, while supply has been slowly normalizing, demand still outstrips supply. This is a condition for higher prices. Yet, resurgent inflation in autos is not likely specifically because high interest rates are constraining and reducing the ability and willingness to pay higher and higher prices. The rate on the 48-month auto loan was last this high in 2002.

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), Finance Rate on Consumer Installment Loans at Commercial Banks, New Autos 48 Month Loan [TERMCBAUTO48NS], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, November 14, 2023.

Finally, domestic banks have also tightened lending standards, likely further constraining the ability to pay higher prices. Lending standards tighten with tighter monetary policy as banks become more risk averse and have a higher cost of funds. This is a Fed effect. From the October, 2023 “Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey on Bank Lending Practices“:

“In a set of special questions, banks were asked to assess the likelihood of approving credit card and auto loan applications by borrower FICO score (or equivalent) in comparison with the beginning of the year. Significant net shares of banks reported that they were less likely to approve both credit card and auto loan applications from borrowers with FICO scores of 620. Moderate and significant net shares of banks reported that they were less likely to approve credit card loan applications and auto loan applications, respectively, from borrowers with FICO scores of 680. In contrast, a modest net share of banks reported being more likely to approve credit card applications from borrowers with FICO scores of 720, while the likelihood of approving auto loan applications to borrowers with FICO scores of 720 was basically unchanged in comparison with the beginning of the year.”

Thus, I claim the Fed deserves at least partial credit for helping to tap the brakes on demand, in the form of ability to pay, in the face of relatively tight inventories. In other words, I find it compelling to create a narrative around a Fed impact that is at least as plausible as the narrative that completely discredits the Fed.

Shelter Inflation

The dynamics of shelter inflation are complex. I grant Stiglitz the point that higher interest rates can exacerbate inflationary pressures by reducing the availability of construction loans needed to increase supply. Interestingly, Stiglitz does not reference the complementary constrain t on supply from existing home owners who refuse to move and incur the cost of mortgages more expensive than their current ones.

Anyway, I will still point out that it was soaring shelter inflation that provided the signal to the Fed that rates were overly accommodative; the episode was a rare moment in Fed history where it acknowledge an inflationary problem from shelter costs. Historically low mortgage rates stoked demand and led to a mini-mania in the housing market. Prices soared practically uncontrollably for homes. Rent soared alongside home prices. I discussed the “housing trigger” for the Fed in “The Federal Reserve Fears On-Going Inflationary Pressures from Rents” and provided more detail in “Inflationary or A Bubble – Housing Prices Help Push A Fed Driving Recession-Pricing for Home Builders.”

I also provided evidence from a home builder about the impact of the Fed on cooling housing prices in “Lennar Corporation: How the Fed Is Cooling Inflation In the Housing Market.”

In other words, the mere fact that one-year leases on rents cause a lag in disinflation is insufficient to dismiss the various ways in which rent inflation forced the Fed to hike and to maintain its hiking campaign. A counterfactual on post-pandemic housing demand and prices in the face of prolonged accommodative policy should not be controversial: we have lived it three times in the span of just one generation.

Core Inflation

Stiglitz noted the following about headline inflation:

“The pandemic-induced inflation was exacerbated further by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which caused a spike in energy and food prices. But, again, it was clear that prices could not continue to rise at such a rate, and many of us predicted that there would be disinflation — or even deflation (a decline in prices) in the case of oil. We were right. Inflation has indeed fallen dramatically in the United States and Europe.”

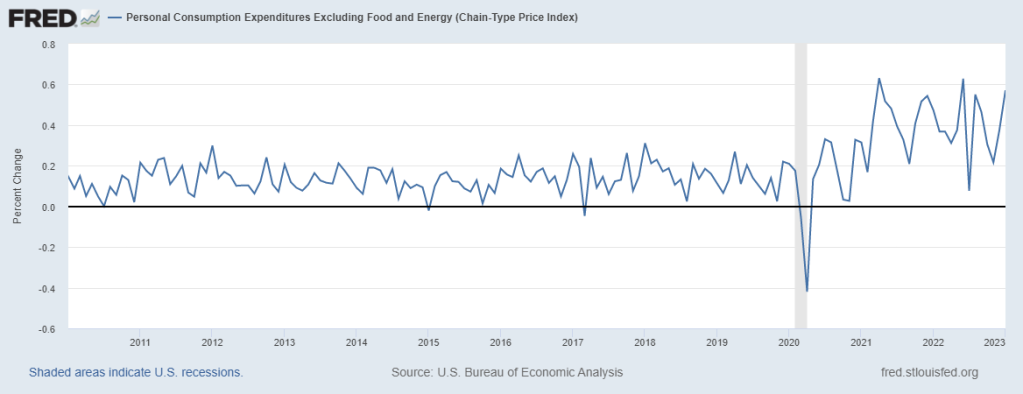

This was a surprising sidebar when the Fed does not set monetary policy by what happens to food and energy. Adding to the distraction, Stiglitz does not label the inflation numbers her uses to compare to the Fed’s target. For the purposes of this discussion I will assume he is referring to core PCE (personal consumption expenditure, excluding food and energy) since it matches the number he uses for September. Yet, I cannot be 100% sure since the 3.7% change in the PCE in September matches the 3.7% headline change in the CPI (consumer price index) for September. This confusion is technically important because the median PCE sits at 4.4%. Core CPI was 4.1% in September, and the October report delivered the tiniest of cooling at 4.0%.

No matter the lens, these levels and incremental declines are hardly an occasion for final victory. While the Fed has every reason to stop hiking rates and watch what happens from here, these numbers do not tell me the Fed can pack up its toys and go home. Stiglitz takes care of that concern by calling the 2% inflation target arbitrary: “There is no evidence that countries with 2% inflation do better than those with 3% inflation; what matters is that inflation is under control. That is clearly the case today.” On the surface, the logic makes sense except that the period of “Great Moderation”, where deflation was the Fed’s biggest concern, was a period where PCE stayed below 2%. We do not have experience in THIS economy with a Fed that overtly allows inflation to stay well above 3%…and the Fed is clearly in no mood to push its luck.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Personal Consumption Expenditures Excluding Food and Energy (Chain-Type Price Index) [PCEPILFE], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, November 14, 2023.

Inflation Expectations

Stiglitz claims that the Fed also had nothing to do with controlling inflation expectations. Unlike the Fed, markets knew that inflation would naturally correct itself. Stiglitz even challenges the protest that inflation expectations remained calm specifically because of trust in the Fed: “…inflationary expectations remained tame. While some central-bank economists claim that this was due to their own forceful response, the data tell a different story. Inflation expectations were muted from early on, because markets understood that the supply-side disruptions were temporary.” Stiglitz took a debatable point and breathed unfounded certainty into it. Stiglitz focuses on the 5-year forward inflation expectation rate:

“Only after central bankers repeated over and over their fears that inflation and inflationary expectations were setting in, and that this would necessitate a long slog entailing high interest rates and unemployment, did inflationary expectations rise. (But, even then, they barely budged, reaching 2.67% for the average of the next five years in April 2021, before falling back to 2.3% a year later.)”

Yet, a different interpretation is plausible and valid regarding the stability in the 5-year forward expectation. It appears the market has a bias to expect disinflation (especially in response to shocks). Starting between 2015 and 2017, the market finally believed the Fed could hold inflation closer to 2.0%. This milestone came after persistent messaging, in different forms, from the Fed on the 2% target. It seems odd to blame the Fed for a brief spike in inflation expectations at the time the Fed started hiking rates. I find it more plausible to interpret the rapid return to previous levels as evidence the market was once again mollified over long-term prospects with a Fed clearly serious about constraining inflationary pressures.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 5-Year, 5-Year Forward Inflation Expectation Rate [T5YIFR], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, November 14, 2023.

Given it appears to take a lot to convince markets the Fed cannot control inflation over the “long-term”, I turned to shorter-term expectations as a more responsive indicator. It turns out that the 3-year consumer expectations peaked right as the Fed finally dropped the notion of transitory inflation in November, 2021. One-year expectations kept rising alongside inflation readings and peaked with a peak in inflation. Thus, it is very possible that the 3-year expectation more accurately reflects sensitivity to the Fed’s actions where it counts: consumers.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Survey of Consumer Expectations

I go into more detail about the mechanics of inflation expectations in “Inflation Expectations and Inflationary Psychology.”

Since short-term expectations can start to bleed into longer-term expectations for inflation, the Fed took a risk management approach when it finally got serious about inflation. Tamp down short-term expectations and remove the risk of perturbing longer-term expectations which could prove harder to control above recent historical ranges.

The Risk Management Approach to Monetary Policy

The question is not whether or not the Federal Reserve should have acted to normalize monetary policy (by picking a non-zero target). The question is how far does/did the Fed need to go. Powell made it abundantly clear that the uncertain (and unprecedented) economic environment put the Fed in a risk management framework. The Fed decided it could not manage policy to the average or expected outcomes in the economy.

For example, a year ago, during the Q&A at a Brookings Institution conference, Powell claimed that monetary policy must take into consideration tail risks and their costs. The Fed collectively had decided that the costs of high inflation outweighed the potential risks of expeditiously hiking rates. The economy has proven so resilient that economists have spent over a year and half pushing out forecasts for a recession, a recession that could have been the main transmission mechanism for monetary policy to tank prices. Now, with the market celebrating the end of rate hikes and declaring victory over inflation, the runway is clear for the soft-landing narrative. I suppose those folks who think the Fed had no influence over inflation will have to conclude that monetary policy is totally meaningless if a recession is not forthcoming!

Conclusion

The inflation debate will never end because participants often bring to the table strong assumptions about the Fed’s capabilities and over-confidence in understanding the intricacies of the post-pandemic economy.

Ultimately, I stand by my long-standing claim that the Federal Reserve acted too slowly as supported by later economic research that I covered last June in “Why Monetary Policy Was Late In Responding to the Pandemic-Era Inflation Surge.” I stake no claim on the ultimate target; I just claim that the Fed needed to start normalizing sooner given what could be known at the time about economic conditions and the massive monetary and fiscal stimulus in the economy. Stiglitz did not explicitly say that he would have preferred the Fed do nothing, but his stance implies as much and feeds the narratives that inflation was never a problem in the first place. Thus, the Fed cannot satisfy anyone, not the inflationistas like myself nor the disinflationistas like Stiglitz….and certainly not the deflationists who held sway for so long going into the pandemic.

Be careful out there!

Canada’s Version of Higher for Longer: Inflation Risks Have Increased

Posted: November 11, 2023 Filed under: Bond market, Canada, Currencies, Economy, oil | Tags: Bank of Canada, Canadian dollar, Federal Reserve, FXC, Invesco CurrencyShares Canadian Dollar Trust, Monetary Policy, Tiff Macklem, United States Oil Fund, USD/CAD, USO 1 CommentThe Bank of Canada (BoC) has completed a 180-degree turn from its goldilocks outlook on inflation from seven months ago. In its October Monetary Policy Report, the BoC lamented that “progress to the 2% [inflation] target is slow.” Governor Tiff Macklem’s opening statement for the accompanying press conference displayed a healthy amount of concern about inflationary pressures (emphasis mine): “further easing in inflation is likely to be slow, and inflationary risks have increased.”

The Bank of Canada is worried about higher energy prices, “structural pressures” in the housing market primarily related to supply shortages (which it acknowledged must first be addressed on the supply side), and “persistence in underlying inflation.” This underlying inflation consists of elevated “near-term inflation expectations and wage growth” and corporate pricing decisions that are “normalizing only slowly.” Core inflation on a year-over-year basis has come down, but the 3-month view shows little downward momentum. Accordingly, the Bank of Canada put the country on notice that it is leaving the door open to future rate hikes because of the stubborn uncertainty in getting inflationary pressures down.

Yet, the BoC did not proceed with a rate hike. Counterbalances to the increased inflation risks remain. Overall supply and demand in the Canadian economy is almost in balance with the trend favoring excess supply. The BoC also downgraded its outlook for economic growth because the economy slowed more than expected back in July; less excess demand exists than expected.

So while the BoC hiked its expectation for inflation from 3% to 3.5% for next year, the central bank is sticking to its longer-run projection of 2% in 2025. Thus, Macklem felt confident in reassuring Canadians: “with clearer evidence that monetary policy is working, Governing Council’s collective judgment was that we could be patient and hold the policy rate at 5%.“ Interest rates will stay higher for longer and the inflation target remains in sight.

Corporate and Government Behavior Working Against Monetary Policy

Companies and Canadian governments in aggregate are not cooperating with the objectives of monetary policy.

Canadian companies are still passing along price increases to consumers faster than normal. From the Monetary Policy Report:

“Corporate pricing behaviour has yet to normalize. Businesses continue to increase prices more frequently and by a larger amount than normal… This may indicate that households and businesses are, respectively, expecting to pay more and charge more for goods and services. High inflation expectations could also feed into wages.”

I assume this dynamic also comes from lingering excess demand which makes consumers less price sensitive. The coming era of excess supply should work counter to this effect.

During the Q&A Macklem pointed out that the fiscal spending plans are working against monetary policy. Aggregate government plans will grow spending by 500 basis points greater than the potential growth of the Canadian economy. Thus, the economy will add more demand than supply. In the past year, growth in government spending was below 2%. Macklem indicated that it would be helpful if fiscal and monetary policy were “rowing together.” The BoC’s forecasts take into account the potential future inflationary pressure from government spending.

The Canadian Dollar Trade

The bump higher in hawkish rhetoric did not benefit the Canadian dollar, perhaps because the BoC maintained its longer-term expectation for inflation. Weakness in the currency Invesco CurrencyShares Canadian Dollar Trust (FXC) or strength in USD/CAD continued until the Federal Reserve’s last policy announcement. Financial markets painted a dovish interpretation to the accompanying news even though it read like nothing materially changed.

I did not expect the drift higher (with high volatility) in USD/CAD as I accumulated a short position. I continue to hold the position as I see two main factors working against my thesis reaching their own individual extremes.

The biggest shift against my original setup was a big increase in the spread on 10-year yields between U.S. and Canadian bonds. Just over a month ago this spread sat at a level that looked like a potential bottom. Shortly thereafter, the bottom dropped out. The spread was last this wide back in March, 2019. This large spread serves advantage to the U.S. dollar over the Canadian dollar. From World Government Bonds:

Oil has also worked against my original thesis. Oil did not stabilize. While it soon spiked higher in response to Hamas’s attack on Israel, selling in oil resumed in about 10 days. Last week, the United States Oil Fund, LP (USO) hit a 3+ month low. While this decline should reduce the Bank of Canada’s fear that higher energy prices will bleed their way into pressures on core inflation, it also works against the Canadian dollar as a commodity currency. I have dropped any expectation on oil although I am net short USO. From TradingView.com:

From a technical perspective, USD/CAD remains well-supported by its uptrending 50-day moving average (DMA) (the red line below). I still expect this uptrend to break to the downside as the extremes working against the Canadian dollar lose steam. To the upside on USD/CAD I have a clear stop loss point above the peak created by the reaction to the Federal Reserve’s November 1st announcement on monetary policy. From TradingView.com:

Be careful out there!

Full disclosure: short USD/CAD, net short USO (short shares, long call spread)

Why the Excitement? A Q&A on Monetary Policy with Generative AI

Posted: November 8, 2023 Filed under: Jobs, Monetary Policy | Tags: CME FedWatch Tool, employment, Federal Reserve, GDP, generative AI, Goldman Sachs, GS, IPO, Jerome Powell, Monetary Policy, NotebookLM, S&P 500, SPY 6 CommentsI left last week’s Federal Reserve conference call with the impression that nothing had changed. I did not hear any new news. Yet, the post-Fed celebration in the stock market continues at the time of writing. While oversold conditions likely primed the pump for the rebound, the enduring nature of the narrative on monetary policy made me wonder what I missed. For this particular review of the Fed, I reached out to generative AI for assistance. I used Google’s experimental NotebookLM as a partner to query the language in the transcript of the conference call; NotebookLM is free and can accommodate all the text in the Fed transcript. I hoped to uncover the secret message that markets saw, but I failed to see or hear. Instead, NotebookLM essentially agreed with my original assessment of the Fed’s message.

Monetary Policy Question and Answer with an AI

The following question and answer with the generative AI in NotebookLM is like a poor man’s substitute for the Fed’s official Q&A session. Each section of dialogue below starts with a quote from Fed Chair Jerome Powell, followed by my question, and then NotebookLM’s response. All quotes are verbatim with some caveats on NotebookLM’s response in curly brackets.

Powell: “We are committed to achieving a stance of monetary policy that is sufficiently restrictive to bring inflation sustainably down to 2 percent over time, and to keeping policy restrictive until we are confident that inflation is on a path to that objective.”

Me: “Does Powell express any confidence that inflation is on the path to meeting its objective of 2%?”

NotebookLM: “No, Powell does not express any confidence that inflation is on the path to meeting its objective of 2%. He says that the Fed will continue to raise rates until inflation is under control, and that the two conditions that would lead the Fed to stop raising rates are (1) if inflation is on a path to the Fed’s 2% target and (2) if the labor market is continuing to broadly cool off and achieve a 4% unemployment rate. He does not say that either of these conditions are likely or happening now.” {That second condition is not directly stated in the transcript. NotebookLM must have picked this up from an external commentary. A more accurate characterization would be to drop the specific, quantified unemployment target}.

Powell: “We are attentive to recent data showing the resilience of economic growth and demand for labor. Evidence of growth persistently above potential, or that tightness in the labor market is no longer easing, could put further progress on inflation at risk and could warrant further tightening of monetary policy.”

Me: “What evidence does Powell cite to demonstrate that recent data show the resilience of economic growth and demand for labor?”

NotebookLM: “Powell cites the following evidence to demonstrate that recent data show the resilience of economic growth and demand for labor:

- GDP growth: Powell cites the strong third quarter GDP figures as evidence that the economy is continuing to expand at a strong pace.

- Employment: Powell notes that the labor market remains very strong, with job openings and labor demand still clearly remaining very strong.

- Inflation: Powell acknowledges that inflation is still high, but he argues that the recent data show that inflation is beginning to moderate.”

Powell: “As for the Committee, we are committed to achieving a stance of monetary policy that’s sufficiently restrictive to bring inflation down to 2 percent over time. And we’re not confident yet that we have achieved such a stance.”

Me: “Does the lack of confidence in achieving a sufficiently restrictive monetary policy leave open the possibility for future rate hikes?”

NotebookLM: “Yes, the lack of confidence in achieving a sufficiently restrictive monetary policy leaves open the possibility for future rate hikes.” {The rest of the response provided an incoherent timeline of Fed action}

Powell: “…the way we’re going to be going into these future meetings is to be just determining the extent of any additional further policy tightening that may be appropriate to return inflation to 2 percent over time” (Powell later reemphasized “it’s fair to say that’s the question we’re asking is, should we hike more”)

Me: This statement suggests that the Federal Reserve has a bias toward hiking rates again. What do you think? Explain your reasoning.

NotebookLM: “Yes, Powell’s statement suggests that the Federal Reserve has a bias toward hiking rates again...However, it is important to note that Powell also said that the Fed will “be humble” in its approach to raising rates, and that it will “listen carefully” to the data. This suggests that the Fed is not committed to a specific path for rate hikes, and that it will be willing to adjust its plans if necessary.” {Rest of answer repeated incoherent timeline even after I asked for a different explanation}

Powell: “the Committee is not thinking about rate cuts right now at all. We’re not talking about rate cuts, we’re still very focused on the first question, which is; have we achieved a stance of monetary policy that’s sufficiently restrictive to bring inflation down to 2 percent over time, sustainably? That is the question we’re focusing on. The next question, as you know, will be for how long will we remain restrictive?”

Me: “How would you assess the odds of a rate cut anytime soon based on this comment and the rest of the transcript?”

NotebookLM: “The odds of a rate cut in the near future are low.

- Powell said that the Committee is not thinking about rate cuts right now at all.

- The Committee is focused on bringing inflation down to 2 percent sustainably.

- The Committee will consider a rate cut if inflation comes down and remains low for an extended period of time.

However, it is important to note that the Committee is also considering other factors, such as the strength of the economy and the labor market. If the economy slows down or the labor market weakens, the Committee may be more likely to consider a rate cut.”

I selected quotes that I thought were most likely to produce some insight into the market’s excitement over the prospects for monetary policy. So just to be thorough, I asked NotebookLM one last question: “Is there anything in this transcript that even hints at the possibility for easier monetary policy in the near future? What about prospects for an end to rate hikes? Explain your reasoning only using content from this transcript.”

NotebookLM concluded: “There is no indication in this transcript that the Fed is considering easier monetary policy or an end to rate hikes.” Its explanation was a repeat response to my previous question.

The Persistent Longing for Easier Monetary Policy

With just two months left in the year and earnings season nearing an end, eyes and prognostications turn to 2024. Year-to-date performance remains positive but the market’s three most dangerous months of the year stained market sentiment. Thus, the persistent longing for easier monetary policy is taking on a new urgency. A recent example came from Goldman Sachs (GS) in predicting a strong year for IPOs in 2024. The main reason for the optimism? Rate cuts! From the Yahoo Finance article “The ‘real IPO reopening’ is coming in 2024: Goldman Sachs“:

“Bruun’s case for IPOs to reemerge stems from a core stance repeated throughout Goldman’s 2024 outlook roundtable on Tuesday: The Federal Reserve will cut rates in 2024. And history says that’s usually an opportune time for the IPO market.

‘When expectation moves such that people are anticipating rate declines and are starting to see rates come down, that’s usually when IPOs open up,’ Bruun said.”

This kind of persistent longing for easier monetary policy is likely to pervade financial markets as the assumption of an end to rate hikes takes deeper root in market sentiment and psychology. If rate hikes have ended then, logically, rate cuts must be imminent.

Still, the Fed will also persist in doing what it can to prevent the market from getting ahead of the Fed’s desire to keep driving inflation to its 2% target. I fully expect Fed jawboning in coming weeks and months to do its best to work against the notion that easier monetary policy is on its way soon. Currently, Fed fund futures do not anticipate any more rate hikes, and the first rate cut comes in June. Both projections are the exact same as they were before the November 1st meeting. Thus this lack of change still has me scratching my head about a renewed excitement over the prospects for monetary policy. From the CME FedWatchTool (the blue boxes indicate the market’s projection for the most likely target for the Fed’s interest rate range the given meeting date in the first column):

The S&P 500

Finally, here is a close-up of the daily trading action in the S&P for perspective on the scale of the market’s recent excitement. Market breadth over this time period went parabolic. (image from TradingView.com)

A Stall in Canada’s Core Inflation Narrative

Posted: September 19, 2023 Filed under: Canada, CPI, Currencies, Economy, Housing | Tags: Bank of Canada, BoC, Canadian dollar, CPI, FXC, Invesco CurrencyShares Canadian Dollar Trust, Statistics Canada, USD/CAD Leave a commentWhat a difference 5 months can make. Canada’s inflation trend has apparently transitioned from a steady decline to a stall. The last two months of failed progress looks like a bottoming process when compared to the previous trend. This stalling also confirms the Bank of Canada’s concern in July about the loss of the benefits of the base effects that helped drive the inflation trend downward. The chart below comes from Statistics Canada in its August CPI report.

Back in April, the Bank of Canada (BoC) described a goldilocks narrative on inflation. This narrative featured the annual change in the Consumer Price Index inflation (CPI) gradually returning to the 2% target at the end of 2024 with economic growth picking up alongside inflation’s downward glide path in 2024. Just two months later in June, the Bank of Canada raised concerns about stubborn inflation and on-going high excessive demand. Accordingly, the BoC took its finger off the pause button on rate hikes and wrote an insurance policy on inflation with one more rate hike. The latest stall in inflation’s trend caused market expectations of a rate hike in October to surge from 23% to 42%.

The Canadian dollar surged along with rate hike expectations. The Canadian dollar was already rallying against the U.S. dollar (USD/CAD) going into the inflation print despite the U.S. dollar’s strength against other major currencies. The chart below shows how the Invesco CurrencyShares Canadian Dollar Trust (FXC) gapped higher at the open but faded from the intraday high. While the intraday action may represent an element of sell on the news, I think the path of least resistance is higher for the Canadian dollar until some new inflation data contradicts the revival of inflation concerns. I sold a small position short on USD/CAD to take advantage of the small fade.

I am not expecting the Federal Reserve’s coming announcement on monetary policy to change the trajectory. Accordingly, I will add to my position if USD/CAD rebounds further.

Drivers of Core Inflation

Core inflation was supported by accelerating rent prices. Ironically, Statistics Canada partially blamed high mortgage rates which are of course higher thanks to the BoC’s rate hikes to fight inflation:

“Shelter prices were up 6.0% on a year-over-year basis in August, after increasing 5.1% in July. Faster growth in shelter prices was led by the rent index, which rose 6.5% year over year nationally, after a 5.5% gain in July. Among other factors, a higher interest rate environment, which may create barriers to homeownership, put upward pressure on the index.”

Presumably, the higher mortgage rates are forcing more people than usual to choose renting over buying and in turn pressuring vacancy rates. Lower vacancy rates tend to push rent prices higher.

I might next need to write about a Canadian inflation conundrum!

Be careful out there!

Full disclosure: short USD/CAD

What Powell Missed In His Jackson Hole Speech Explaining Inflation’s Drivers

Posted: August 25, 2023 Filed under: Bond market, Economy, Monetary Policy, Stock Market | Tags: Federal Reserve, iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond ETF, Jackson Hole, Jerome Powell, Monetary Policy, S&P 500, SPY, TLT 2 CommentsFederal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell included a neat and tidy explanation of the drivers of inflation in today’s Jackson Hole Speech titled “Inflation: Progress and the Path Ahead.” However, Powell missed one of the key drivers that fanned the flames of all the other drivers: the Fed held interest rates too low for too long and left overall monetary policy extremely accommodative long after it was needed. In early June I laid out that case in detail combining the research of economists Gauti B. Eggertsson (Brown University) and Don Kohn (Hutchins Center on Fiscal & Monetary Policy, Brookings Institution) and my previous claims about the Fed’s role in creating high inflation. As a reminder here are the key points for the case of Fed-driven inflation:

- The Fed’s revised monetary policy framework in 2020 contained an inherent inflationary bias.

- The Fed relied too heavily on hawkish hints in the months leading into the lift-off for monetary policy.

- The Fed recognized too late that the labor market was sufficiently tight for higher rates.

Powell made no mention of any of these factors in his Jackson Hole speech. Instead, Powell provided a one sentence summary of the inflation narrative: “The ongoing episode of high inflation initially emerged from a collision between very strong demand and pandemic-constrained supply.” Even in describing the path to lower inflation, Powell avoided saying that the Fed needs to unwind overly accommodative monetary policy: “By the time the Federal Open Market Committee raised the policy rate in March 2022, it was clear that bringing down inflation would depend on both the unwinding of the unprecedented pandemic-related demand and supply distortions and on our tightening of monetary policy.” Inflation has to unwind itself along with the assistance of tightening policy.

Powell went on to provide a very familiar narrative about inflation:

- The Russian invasion of Ukraine has driven up headline inflation.

- “Demand for vehicles rose sharply, supported by low interest rates, fiscal transfers, curtailed spending on in-person services, and shifts in preference away from using public transportation and from living in cities. But because of a shortage of semiconductors, vehicle supply actually fell.” At least Powell acknowledged low interest rates helped drive excess demand for vehicles.

- “In the highly interest-sensitive housing sector, the effects of monetary policy became apparent soon after liftoff. Mortgage rates doubled over the course of 2022, causing housing starts and sales to fall and house price growth to plummet. Growth in market rents soon peaked and then steadily declined.” Here Powell chose to focus on the impact of higher rates on housing which of course implies that lower rates supported housing demand. He avoided noting how unnaturally low interest rates drove the housing market to mania levels of demand and pricing.

- “Part of the reason for the modest decline of nonhousing services inflation so far is that many of these services were less affected by global supply chain bottlenecks and are generally thought to be less interest sensitive than other sectors such as housing or durable goods. Production of these services is also relatively labor intensive, and the labor market remains tight.” Nonhousing services inflation presents the Fed with its most troublesome driver of inflation. Powell noted that inflation in this sector has “moved sideways” since monetary tightening began.

A stronger than expected economy is the upshot to the current inflation story. This above trend economic growth could force the Fed to continue hiking rates higher and for longer than current expectations. In fact, this economic strength is the exact opposite of what so many economists, pundits, and analysts have expected for 18 months or so. The most anticipated recession in U.S. history just refuses to materialize.

The current uncertainty leaves financial markets nervous. The U.S. dollar (DXY) is stronger than expected at this part of the cycle, the entire rate curve is moving higher, and the stock market looks wobbly. The NASDAQ (COMPQ) and the S&P 500 (SPY) have returned to their last highs preceding Jackson Hole 2022. What I have called the “summer of loving stocks” has already lost all its gains from July. August is just the first month of the three “most dangerous” months in the stock market. So even as the stock market approaches oversold trading conditions, obligatory rebounds may be insufficient to stave off a rollback of all the summer gains.

The S&P 500 (SPY) is confirming a failure at 50DMA resistance on its way to what looks like a more direct test of support from the high prior to Jackson Hole 20222.

The iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond ETF (TLT) is challenging its lows from October and November. A further breakdown could trigger a fresh wave of selling in the stock market.

Be careful out there!

Full disclosure: long TLT put spread

Is the British Pound Topping Despite Lingering Strength in UK Core Inflation?

Posted: July 21, 2023 Filed under: Currencies, United Kingdom | Tags: British pound, CPI, CPIH, GBP/USD, inflation expectations, Office for National Statistics, technical analysis, United Kingdom Leave a commentExpectations can define reactions to news in financial markets. Forecasts for June inflation in the UK ran a little hot after May’s inflation report caught forecasters flat-footed. So when June inflation numbers came in lower than expected, financial markets experienced a sharp bout of relief. Expectations for rate hikes from the Bank of England moderated and took the British pound (GBP/USD) down with them. While the pound drifted lower after May’s inflation report, the pullback this time around was abrupt and sharp. Yet, the market may have overreacted given core CPIH (Consumer Prices Index including owner occupiers’ housing costs) continues to trend higher (core CPIH excludes energy, food, alcohol & tobacco). Core CPIH barely budged in June and left the uptrend intact even as consumer and headline inflation has clearly peaked.

The above graph shows that services inflation is the main culprit keeping core CPIH in an uptrend. Core CPIH dropped from 6.5% in May to 6.4% in June. Since May was a 30-year high, I am particularly unimpressed by the “pullback” in the core inflation rate. The Core CPI (Consumer Prices Index) dropped from 7.1% in May, a 31-year high, to 6.9% in June.

Food and energy inflation is coming off extreme levels. Food inflation is coming off a peak 19.2% in March, 2023. Fuel prices are outright plummeting, falling 13.1% in May and 22.7% in June.

The British Pound Cools with Inflation

The cooling overall inflation numbers cooled the heels of the British pound which has been on quite a streak since the bond and currency crisis 10 months ago. GBP/USD, also Invesco CurrencyShares British Pound Sterling Trust (FXB), was falling off a near 16-month high coming into the inflation print. The inflation report greased the skids on the way to an important test of the uptrending 20-day moving average (DMA). That line has held as support since the beginning of June and has been important support since early March.

Source: TradingView.com

For now, I am trading for a bounce from the 20DMA and prepared to to accumulate a larger position for a test of 50DMA support. The overall drivers of sterling strength seem intact as long as core inflation is uptrending or even just sticky. The Bank of England will have to remain as hawkish as ever.

Of course, the upcoming meeting of the U.S. Federal Reserve is a major wildcard. If the Fed manages to get hawkish enough to scare some fresh strength into the U.S. dollar, then I will have to drop my current trading strategy.

Regardless, the uptrend in the pound should at some point end in the coming months. This recent weakness in the currency could be the beginning of the end.

Be careful out there!

Full disclosure: long GBP/USD

Base Effects Add to the Bank of Canada’s Inflation Concerns

Posted: July 13, 2023 Filed under: Canada, Economy, Monetary Policy | Tags: Bank of Canada, base effects, FXC, Invesco CurrencyShares Canadian Dollar Trust, Monetary Policy, USD/CAD 1 CommentLast month, the Bank of Canada worried about inflation staying more persistent than expected and decided to release the pause button on rate hikes. In this month’s Monetary Policy Report, the Bank of Canada added “base effects” to its list of concerns about stubborn inflationary pressures (emphasis mine):

“While CPI inflation has come down largely as expected so far this year, the downward momentum has come more from lower energy prices, and less from easing underlying inflation. With the large price increases of last year out of the annual data, there will be less near-term downward momentum in CPI inflation. Moreover, with three-month rates of core inflation running around 3½-4% since last September, underlying price pressures appear to be more persistent than anticipated. This is reinforced by the Bank’s business surveys, which find businesses are still increasing their prices more frequently than normal.”

I have seen more and more references to base effects regarding U.S. inflation. In the previous two years, base effects could be used to dismiss inflation’s threat. This year, base effects from more challenging comparables are looming as the end of the tailwinds for disinflation (on a year-over-year basis). The timing is poor. As the Bank of Canada noted, underlying inflation has gone nowhere for almost a year. At this point, sticky inflationary pressures cloak more uncertainty around prior inflation expectations:

“In the July MPR projection, CPI inflation is forecast to hover around 3% for the next year before gradually declining to 2% in the middle of 2025. This is a slower return to target than was forecast in the January and April projections. Governing Council remains concerned that progress towards the 2% target could stall, jeopardizing the return to price stability.”

Surprisingly, markets took the news in stride. At the same time the U.S. stock market celebrated a pleasing report on U.S. June inflation, the Bank of Canada’s rate hike did not dampen spirits about the prospects for a more dovish Federal Reserve. Currency markets reacted as though the Fed might even be closer to rate cuts as losses in the US. dollar continued apace.

In fact, the market almost seemed to skip right over the Bank of Canada’s news. While majors like the euro and the British pound rallied all day against the U.S. dollar, the Canadian dollar enjoyed just brief intraday strength in the wake of the Bank of Canada’s decision to hike rates another 25 basis points. At the time of writing, USD/CAD is only just now returning to its low point following the rate hike (and looks stalled right at support).

On a daily basis, the Canadian dollar looks set to resume its momentum against the U.S. dollar IF USD/CAD breaks below yesterday’s low. Otherwise, a countertrend rebound could take USD/CAD right back to downtrending resistance at the 50-day moving average (DMA) (the red line below) as the next move.

I remain bearish on USD/CAD (bullish the Canadian dollar), and I expect rallies to continue to fail just as they have since September. The path downward on USD/CAD (upward for Invesco CurrencyShares Canadian Dollar Trust (FXC)) has been slow and choppy yet ever so slightly biased toward more relative strength for the Canadian dollar. The next major test comes with the Federal Reserve’s meeting later this month. More Fed hawkishness at that time could refresh the U.S. dollar against all majors for a spell.

Be careful out there!

Full disclosure: no positions

Why Monetary Policy Was Late In Responding to the Pandemic-Era Inflation Surge

Posted: June 10, 2023 Filed under: Economy, Monetary Policy | Tags: Brookings Institution, Don Kohn, Federal Reserve, Gauti B. Eggertsson, James Bullard, Jerome Powell, Monetary Policy, pandemic, Policy Framework, Robert Kaplan, unemployment, vacancy-unemployment ratio 2 CommentsValidation That Monetary Policy Was Overly Accommodative for Too Long