Fed’s Daly: The Market Is Wrong About A Hump in 2023 Fed Rates

Posted: October 6, 2022 Filed under: commodities, Economy, iron ore, Monetary Policy, oil, Salaries | Tags: BHP, BHP Group, Fed Fund Futures, Federal Reserve, Mary Daly, Monetary Policy, real wages, UGA, United States Gasoline Fund 4 CommentsThe Federal Reserve board governors continue to stay on message, reminding the market over and over about its serious intention to fight inflation. San Francisco President Mary Daly has been particularly articulate on the Fed’s plan and what likely lies ahead. In an interview with Bloomberg Finance today, Daly informed financial markets that they are “wrong” to project what the interviewr called a “hump” in rate expectations. This hump is a peak sometime in 2023 with rate cuts to follow soon after. The current view from CME FedWatch has rates peaking from the February through June, 2023 meetings with a rate cut in July.

Daly’s steadfast perspective is important to remember every time the stock market rallies in anticipation of peak inflation and/or a “Fed pivot.” Indeed, Daly warned that the Fed needs to be prepared for inflation to be more persistent than expected. For context, Daly was one who was unwilling to predict peak inflation ahead of what turned out to be the “CPI shocker” that delivered a surprise of higher core inflation. Part of Daly’s persistence comes from what she and the Fed see as inflation’s greater potential for economic harm than the short-term consequences of normalizing monetary policy. Daly noted that over two years real wages have fallen 9%. She even shared an anecdote of a worker who told her about how he “loses” money when he goes to buy something with his earnings (an anecdote that speaks to nominal wages failing to keep up with nominal increases in prices).

Other interesting nuggets from the interview:

- Rates are probably now around the neutral rate, and the Fed needs to get slightly restrictive.

- The length of time rates stay neutral (or slightly restrictive) is more important than the specific level.

- 50% of today’s inflation is driven by demand (thus justifying the Fed’s desire to get slightly above neutral), 50% from supply.

- Daly refused to take the bait on the question of whether the Fed was purposely trying to induce a recession, trying to force losses on the stock market, or intent on hiking rates until something breaks.

- Daly insisted the Fed is forward-looking and recognizes lagging indicators of inflation.

- Daly pushed back on the notion the Fed needs to coordinate with global central banks. She insisted that the Fed must stick to its domestic dual mandate.

While the signs a few months ago were clear from commodity prices that the Fed’s actions were impacting inflation, the recent strength in oil threatens to rekindle inflation fears from the average person. For example, gas prices look like they are already done declining. The United States Gasoline Fund, LP (UGA) broke out today. UGA looks like it double-bottomed in September.

The recent downtrend in United States Gasoline Fund, LP (UGA) came to an end this week with a powerful breakout above 50 and 200DMA resistance.

Similarly, diversified commodities producer BHP Group (BHP) looks like it is holding a bottom in place since late last year.

BHP Group (BHP) has so far held its lows from a year ago. While upside may be limited, BHP also looks like it is done going down for now.

If these bottoms are indicative of what is ahead, then any soft readings in the near-term inflation numbers could be, well, transitory… (tongue-in-cheek intended!)

Be careful out there!

Full disclosure: long BHP

The Fed’s Hawkish Pressure Is Working Against Inflation

Posted: July 3, 2022 Filed under: Agriculture, Bond market, commodities, iron ore, Materials, Monetary Policy, Steel | Tags: 30-year fixed rate mortgage, BHP, BHP Group Limited, corn, FCX, Federal Reserve, Freeport McMoRan, lumber, RIO, Rio Tinto, TIPS, Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities, XME 5 CommentsThe Federal Reserve has stuck by its aggressively hawkish stance despite massive pains suffered in financial markets and growing risks of a recession. Markets are so convinced by and so scared of the Fed that they have raced far ahead of current policy to anticipate a lot of price hikes ahead. Soaring mortgage rates are one example of the Fed’s sharp impact. The 30-year fixed rate mortgage was last this high during the recession of the Great Financial Crisis (GFC).

![Source: Freddie Mac, 30-Year Fixed Rate Mortgage Average in the United States [MORTGAGE30US], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; June 28, 2022.](https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/fredgraph.png?g=RiKx)

These suffocating mortgage rates are an important sign of victory for a Fed whose primary inflation concerns come from housing.

An even clearer sign of victory comes from the bond market, specifically the breakeven rates on five- and 10-year Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS). Reuters reported that these TIPS “slid to 2.636% and 2.362%, respectively, a level last seen in September 2021.” Nancy Davis, managing partner and chief investment officer at Quadratic Capital Management LLC, accordingly observed that “the breakeven market, the difference between TIPS versus regular Treasuries, is dramatically downward sloping. It’s barely above the Fed’s long-term average (inflation) target of 2%.” In other words, the bond market is already anticipating that the Fed’s aggressive push to normalize monetary policy and fight inflation will work.

A broad swath of commodities and commodity-related stocks are suffering under the weight of the Fed’s success. The charts below are just a sample: diversified commodities producer BHP Group Limited (BHP), iron ore producer Rio Tinto (RIO), copper producer Freeport McMoRan (FCX), and the metals and mining ETF (XME) (charts from TradingView.com). Even agricultural commodities like corn and lumber look like they have topped. Perhaps these declines represent the early signals of a recession. If so, those concerns may wait for a post-inflationary day.

BHP printed a double-top in 2022 BELOW the 2021 highs.

RIO topped out in 2022 well below 2021’s highs. It now trades at the November, 2021 low and is at risk of challenging the November, 2020 low.

FCX is close to erasing ALL its 2021 gains.

The SPDR S&P Metals & Mining ETF (XME) quickly reversed its entire 2022 breakout.

Spot corn prices closed below the uptrending 200-day moving average for the first time since January. The topping formation for 2022 looks like the dreaded head and shoulders top (shoulders in March and June, the head in April).

Lumber prices topped out in 2022 well below the 2021 highs.

Be careful out there!

Full disclosure: no positions

Persistently Elevated, Unactionable Inflation

Posted: June 10, 2022 Filed under: CPI | Tags: Bonawyn Eison, CNBC, CPI, Fast Money, Federal Reserve, Lindsey Piegza 4 CommentsBonawyn Eison, CNBC Fast Money commentator, used the phrase “persistently elevated, unactionable inflation” to describe the current inflationary cycle. Ahead of the disappointing report on May inflation, Eison pushed back on the “peak inflation” narrative as part of an attempt to “reverse engineer” a reason to buy the stock market. While he framed the desperate gaze over the inflation horizon in stock market terms, his characterization is quite appropriate for today’s overall inflation problem. Inflation has been persistent thanks to a powerful convergence of massive monetary stimulus, equally potent fiscal stimulus, and a host of economic disruptions. In turn, inflation promises to remain elevated for quite some time. Perhaps most importantly, the tools for fighting inflation are small compared to the size and the near intractability of the problem. For the Federal Reserve in particular the path to fighting inflation is fraught with the economic perils of stagflation.

The lure of the “peak inflation” narrative has been strong since the report on March inflation. The appeal is natural because of the sense that over time all economic conditions revert to the mean (or the average). However, the rush to declare the end of today’s problem with inflation has been particularly meaningful because it occurs in the middle of a desperate, global desire to return to some form of the “normalcy” we (think) we enjoyed before the pandemic. To their credit, various Federal Reserve members tried to soft pedal the idea of peak inflation, including the San Francisco President back in late April. They have remained nearly uniform in their stated resolve to focus on fighting inflation. The path from 8.6% to anything close to the Fed’s comfort zone does not start with hoping for a peak in inflation.

That 8.6% is where the headline Consumer Price Index (CPI) hit in May. Inflation hurtled March’s 8.5% for a new high for this inflationary cycle. The “peak inflation” crowd might now think surely inflation cannot go any higher from here. Perhaps this hope works out this time, but it matters little in the face of persistent and elevated inflation. Moreover, on the same Fast Money episode featuring Eison’s commentary, Lindsey Piegza, chief economist at Stifel, made an excellent point about the lagging nature of the CPI. Piegza pointed out that the worst impacts of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the COVID lockdowns in China have yet to hit the CPI. If so, CPI may not continue to increase, but inflation will remain high for quite some time.

The broad-based nature of the May CPI increases suggests that inflation will indeed remain far above the Fed’s comfort zone for quite some time. Both the month-over-month and, of course, year-over-year inflation numbers were elevated across major categories (numbers are monthly and then year-over-year):

- Food: 1.0% and 8.6%

- Energy: 3.9% and 34.6%

- All items less food and energy: 0.6% and 6.0%

- New vehicles: 1.0% and 12.6%

- Used cars: 1.8% and 16.0%

- Shelter: 0.6% and 5.5%

The persistent rise in shelter costs is particularly notable given the Fed’s sudden sense of urgency on normalizing monetary policy implicitly came from housing costs.

I see at least one lesson from these numbers: inflation will not peak until it peaks. In other words, there is little point in straining the eyes over the horizon seeking the end of this inflationary cycle. Whatever the specific numbers, inflation here in the U.S. and across many nations promises to be persistent and elevated and will frustrate the economic agent who try to act against it without causing other economic fallout.

Be careful out there!

Jim Bianco: “Arguably One of the Worst Forecasts In Fed History”

Posted: April 8, 2022 Filed under: Bond market, Monetary Policy | Tags: Federal Reserve, iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond ETF, Jim Bianco, Monetary Policy, TLT Leave a commentI thought *I* was critical of the Fed waiting so long to start normalizing monetary policy! Jim Bianco, President of Bianco Research, LLC, took criticism of the now moribund “transitory inflation” narrative to a new extreme. In an interview with CNBC’s Fast Money, Bianco took the Fed to task for what he called “arguably one of the worst forecasts in Federal Reserve history.” As a result, the Fed finds itself stuck with an inappropriately loose monetary in the middle of a high price, supply-constrained economy. The Fed intends to dampen demand through higher borrowing costs and lower stock prices (the wealth effect). The historic gap between job openings and the number of unemployed gives the Fed plenty of room to hike rates (until something breaks).

Fast Money invited Bianco after noticing an extended twitter thread that also took the stock market to task for ignoring rate hike risks. Bianco noted the dichotomy between a bond market that understands the Fed is more focused on controlling prices than growth, and a stock market that keeps doing its best to ignore the prospects. Bianco’s charts show that “the carnage is epic” in the bond market: “This is not only the worst bond market in our career (total return) but might be the worst of our lifetime.” Meanwhile, Bianco insists that what is ahead will hurt all financial assets.

The Trade

In “The Market Breadth“, I specialize in market opportunities at the extremes of behavior. So hearing that the bond market is suffering historic losses actually intrigues me. I suspect that sometime in the middle of an aggressive tightening cycle, bonds will present a generational buying opportunity. I am not a student of bond markets, so I will have to rely on the technical signals from a proxy bond instrument like the iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond ETF (TLT). The weekly chart below suggests that the opportunity zone on TLT sits somewhere between the 2013 lows (government shutdown drama) and the lows of the financial crisis. I assume the lows of 2018 will be an insufficient stopping point, but I will watch closely for a bounce at that level. On the way down, I have been fading TLT rallies with put options.

Be careful out there!

Full disclosure: no positions

The Federal Reserve Fears On-Going Inflationary Pressures from Rents

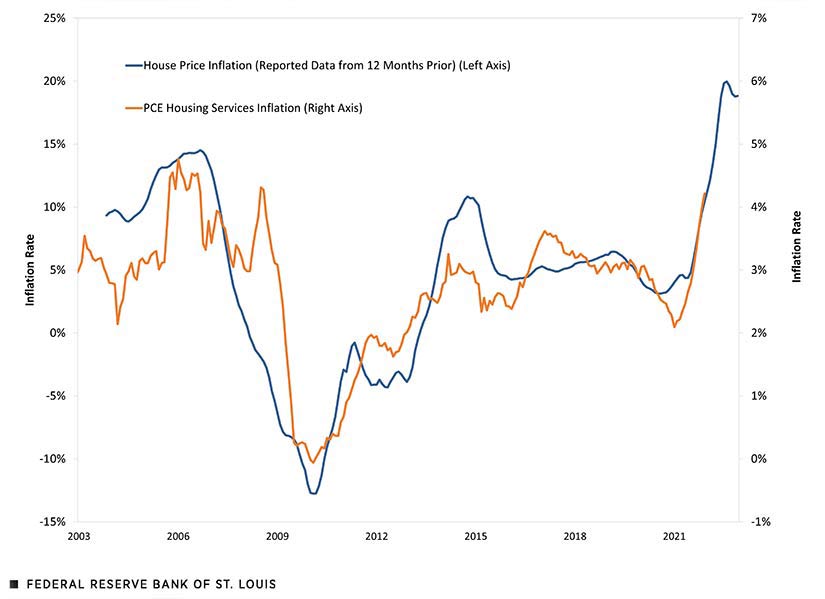

Posted: April 3, 2022 Filed under: Central bank, Housing, Monetary Policy | Tags: Federal Reserve, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, housing prices, Monetary Policy, PCE, rent, services 1 CommentI recently complained about the Fed’s belated sense of urgency in trying to get inflation under control. The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis shed some light on the specific points of concern for the Federal Reserve. In an economic article titled “Breaking Down the Contributors to High Inflation“, the St. Louis Fed described a 12-month lag for housing price dynamics to feed into rents. Given the soaring prices of housing for over a year, rents are due to soar from already high levels for at least the next year or so. Here is the instructive chart:

The Fed’s core concern comes from the out-sized influence of housing services on the PCE (Personal Consumption Expenditures): “Given that housing services constitutes the largest subcomponent of PCE, accounting for roughly 18% of total consumption expenditures, the impact of housing services inflation on overall PCE inflation is always significant.” In other words, I interpret the Fed’s recent religion on normalizing interest policy as a belated attempt to cool down price appreciation in the housing market.

The St. Louis Fed also put this concern in context by comparing today’s inflation with the inflation from the last economic expansion from July 2010 to January 2020. Interestingly each of the three components of the PCE – durable goods, non-durable goods, and services – have contributed around the same amount of extra inflationary pressure in absolute terms, ranging from 1.46 to 1.71 percentage points. However, with a 65% of total consumption expenditures, the promise of on-going upward pressure on services inflation promises to drive the overall PCE ever higher. The Fed finally could no longer sit still on rates.

(For a good read on belated inflation concerns, review Jason Furman’s critique of the economics profession: “Why Did Almost Nobody See Inflation Coming?“)

Be careful out there!

Full disclosure: no positions

Transitory Complete: Fed Chair Jay Powell Gets Comfortable With the Inflation Hawks

Posted: March 22, 2022 Filed under: Automobiles, Economy, Government, Monetary Policy | Tags: Federal Reserve, Jerome Powell, new car prices, recession, used car prices 9 CommentsTransitory Complete

Pandemic-era inflation pressures were not transitory after all. The inflation watchers I follow never believed the narrative given the Fed’s insistence on maintaining historically accommodative policy well past its expiration date. Indeed, the transitory in the economy turned out to be the deflationary psychology of Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell.

The journey has been quite a ride for Fed-speak. In July 2020, Powell reassured an economy in lockdown shock that the Fed is “not thinking about thinking about raising rates.” When murmurs and then gripes about creeping inflation emerged in early 2021, Powell insisted inflation pressures would be transitory. In late April of that year, Powell explained the theory at that time behind transitory inflation. Transitory stretched out longer and longer and longer, until finally in December, 2021 testimony Powell essentially asked everyone to leave him alone about the unfortunate and untimely phrase. Now, with inflationary pressures worsening, Powell has found inflationista fervor. Powell even declared that the Fed is ready to take rates higher than the neutral rate. The mad scramble has begun; the Fed wants to get a raging fire under control.

A Pivotal Speech

Today, March 21, 2022, Powell gave what I think is the pivotal speech of his career as Fed chair. With the appropriately ominous title “Restoring Price Stability“, Powell started with this proclamation to the 38th Annual Economic Policy Conference National Association for Business Economics assembled in Washington, D.C. (emphasis mine):

“…the current picture is plain to see: The labor market is very strong, and inflation is much too high. My colleagues and I are acutely aware that high inflation imposes significant hardship, especially on those least able to meet the higher costs of essentials like food, housing, and transportation. There is an obvious need to move expeditiously to return the stance of monetary policy to a more neutral level, and then to move to more restrictive levels if that is what is required to restore price stability. We are committed to restoring price stability while preserving a strong labor market.”

For the folks who might still be in transitory thinking, Powell went on to clarify “…the inflation outlook had deteriorated significantly this year even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.”

In racing against the wildfire, Powell and the Fed have an ambitious goal. They want to avoid a recession by tapping the brakes on excessive demand in the economy just enough to gently match limited supply. The strong labor market is both a blessing and a curse in this effort. Powell did not use the term “wage-price spiral” inflation spiral”, but he essentially described such a potential dynamic for today’s economy. Companies are struggling to hire. Employees are shifting into new jobs to gain higher wages.

“There are far more job openings going unfilled today than before the pandemic, despite today’s unemployment rate being higher. Indeed, there are a record 1.7 posted job openings for each person who is looking for work. Record numbers of people are quitting jobs each month, typically to take another job with higher pay. And nominal wages are rising at the fastest pace in decades, with the gains strongest for those at the lower end of the wage distribution and among production and nonsupervisory workers”

Powell summarized: “Overall, the labor market is strong but showing a clear imbalance of supply and demand.” Thus, the Fed feels compelled to “moderate demand growth.” In the process the Fed hopes that the labor market’s very strength will withstand a period of aggressive monetary tightening.

Powell explained that the big surprise came from the stubborn persistence of “supply-side frictions.” The economy cannot handle the rapacious demand in today’s economy without sending prices ever higher. In turn, spiraling inflation threatens to erode wage gains especially for lower-income workers.

No Time to Wait Anymore

Interestingly, Powell provided automobile prices as a good example of the inflation problem. There was a time when commentators insisted soaring car prices would be transitory. Auto prices are now transitory complete. Powell lamented “production remains below pre-pandemic levels, and an expected sharp decline in prices has been repeatedly postponed.” Prices for new cars soared almost all of last year and suddenly look ready to take off again. Used car prices soared even more and could lift again if new car prices rev up again. Regardless, no “base effects” here as worker’s wage gains look sure to come under more pressure.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: New Vehicles in U.S. City Average [CUSR0000SETA01], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, March 21, 2022.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: Used Cars and Trucks in U.S. City Average [CUSR0000SETA02], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, March 21, 2022.

These mounting pressures have forced the Fed’s hand. The Fed senses it has no time to wait anymore. The Fed is no longer content to wait for the conventional expectations of normalization to bear fruit. In an inflation emergency the Fed needs to act now… (emphasis mine).

“It continues to seem likely that hoped-for supply-side healing will come over time as the world ultimately settles into some new normal, but the timing and scope of that relief are highly uncertain. In the meantime, as we set policy, we will be looking to actual progress on these issues and not assuming significant near-term supply-side relief.”

Inflation is so strong now that Powell has to look out 3 years to envision inflation returning to the Fed’s target of 2%: “I believe that these policy actions and those to come will help bring inflation down near 2 percent over the next 3 years.”

Recession? What Recession?

No Federal Reserve has ever predicted a recession. The central agent trying to command the economy has a vested interest in projecting utmost confidence in its navigation abilities. Accordingly, Powell looked to history as proof that the Fed can pull off the spectacle of the soft landing for the economy:

“I believe that the historical record provides some grounds for optimism: Soft, or at least soft-ish, landings have been relatively common in U.S. monetary history. In three episodes—in 1965, 1984, and 1994—the Fed raised the federal funds rate significantly in response to perceived overheating without precipitating a recession…In other cases, recessions chronologically followed the conclusion of a tightening cycle, but the recessions were not apparently due to excessive tightening of monetary policy. For example, the tightening from 2015 to 2019 was followed by the pandemic-induced recession.”

The Fed is also encouraged by an economy “well positioned to handle tighter monetary policy.”

Powell formerly insisted the Fed would hold rates lower for longer in order to achieve an exceptionally low unemployment rate. The current path flips to the opposite direction. The Fed is willing to go right past the point of neutral rates to get the fire under control: “if we determine that we need to tighten beyond common measures of neutral and into a more restrictive stance, we will do that as well.”

Transitory complete. Bring on the inflation hawks.

Be careful out there!

The Fed Asks “What Inflation?”

Posted: June 23, 2014 Filed under: Economy, Government, Monetary Policy | Tags: CPI, Federal Reserve, Monetary Policy, PCE Leave a commentLast week, headlines and pundits were hot and bothered about the potential for the Federal Reserve to fall behind the curve on inflation. While my on-going assumption is that the Fed will indeed chose much higher inflation rather than risk ending the economic recovery with higher rates, I think the current hand-wringing by some is premature. In fact, it seems more the result of either boredom with the Fed’s business as usual policy stance and/or the anxiety on the part of some stock market bears looking for any kind of catalyst to shake the market out of its low volatility slumber.

I was so surprised at all the hand-wringing over a “business as usual” policy statement that I rolled the tape on the press conference. I was wondering what I missed, I actually listened to the conference call a second time (yes, it was painful). The experience made me even more convinced the market over-reacted just as much as it did when Yellen carelessly suggested rates might increase earlier than the late 2015 market projection.

Recent inflation numbers apparently increased expectations that the Fed might show a more hawkish tone. This is reflected best in the first question of the press conference from Steve Liesman of CNBC:

“Is every reason to expect, Madam Chair, that the PCE inflation rate, which is followed by the Fed, looks likely to exceed your 2016 consensus forecast next week? Does this suggest that the Federal Reserve is behind the curve on inflation? And what tolerance is there for higher inflation at the Federal Reserve? And if it’s above the 2 percent target, then how is that not kind of blowing through a target the same way you blew through the six and a half percent unemployment target in that they become these soft targets?”

This was a leading question, especially considering that Yellen made it very plain in her introduction that the inflation readings remain benign. Moreover, long-term expectations for inflation remain tame (also see the Fed’s latest projections). Most importantly, the year-over-year change in the PCE, the Personal Consumption Expenditure, reached the 2.0% target in early 2012 only to quickly plunge from there. Not only might it be premature to project a 2% reading for next week’s release, but there is nothing to suggest that this time is different. The Federal Reserve has the least control over the non-core prices of food and energy, so the escalation of violence and turmoil in Iraq is definitely not the kind of event that the Fed would try to offset with monetary policy.

The Fed still can’t tease the market into sustaining pre-recession inflation levels…

Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve

Perhap’s Yellen’s poor response ignited the flames of disappointment. Yellen did not address PCE directly and instead talked about the noise in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) while reiterating the Fed’s standard guidance on inflation:

“So, I think recent readings on, for example, the CPI index have been a bit on the high side, but I think it’s–the data that we’re seeing is noisy. I think it’s important to remember that broadly speaking, inflation is evolving in line with the committee’s expectations. The committee it has expected a gradual return in inflation toward its 2 percent objective. And I think the recent evidence we have seen, abstracting from the noise, suggests that we are moving back gradually over time toward our 2 percent objective and I see things roughly in line with where we expected inflation to be.”

Ironically, Yellen could have just pointed to the longer-term trend in the CPI. This view dominates any shorter-term noise….

The overall trend on CPI continues to point downward

Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve

The most bizarre part of the buzz on the Fed’s supposed willingness to ignore inflation is that Yellen re-affirmed, re-emphasized that the Fed is all about meeting its price target. It will not tolerate deviations in EITHER direction for long:

“…we would not willingly see a prolonged period in which inflation persistently runs below our objective or above our objective and that remains true. So that hasn’t changed at all in terms of the committee’s tolerance for permanent deviations from our objective.”

This was Yellen’s response to Liesman asking about the Fed’s tolerance for higher-than-target inflation.

I feel irony in my skepticism about a Fed ignoring a budding inflation threat: this is the core scenario that has kept me long-term in the gold (GLD) and silver (SLV) trades. My thesis/assumption back in 2009/2010 was that the Federal Reserve would be extremely reluctant to tighten policy even as the economy strengthened out of fear that rate hikes would quickly kill the economy. By the time the Fed was ready to hike rates, the “inflation genie” would already be out the bottle. Granted, I am not nearly as rabid about this view, especially since I have come to appreciate the deep entrenchment of the lingering post-recession deflationist psychology in the economy.

So, overall, I am very skeptical that this episode is the long-awaited lift-off of inflation and a lagging Fed. I actually think the Fed is right to look through the current “warming” in inflation readings, and I think it will find vindication just as the Bank of England did during a similar episode under former Governor Mervyn King. When the Fed asks “what inflation”, I find myself surprisingly agreeing for now…

To me, the data do not support the notion that broad-based inflation is taking hold in the economy. We do not even have wage pressures, not to mention all the slack that remains in the economy as evidenced in part by extremely low levels of housing production. Just do a web search or read mainstream financial magazines to see anecdotally how many people are still worried about the sustainability of the so far very weak housing recovery. I find it hard to believe we will get strong inflation with all this weakness and deflationary fears. On the commodity side, copper and iron ore have experienced major price declines in recent months that also fly in the face of any kind of sustained inflationary pressure in the economy.

Full disclosure: long GLD, SLV.

Inflation May Be Dead, But Inflation Watch Is Not

Posted: June 15, 2013 Filed under: Australia, commodities, Monetary Policy | Tags: Federal Reserve, inflation rate, Reserve Bank of Australia 2 CommentsThings have been pretty quiet around here. Every now and then I see a story about rising prices somewhere in the world and think the story would make a great quick post for Inflation Watch. However, I usually do not feel the same sense of urgency I had from 2008 through about 2011 when I felt that rapid inflation was the imminent result of extremely accomodative monetary policy. Everywhere I look, commodities continue to decline in price. Most commodities reached a peak in 2011 and that peak of course had me convinced more than ever that inflation was soon to be a big problem.

Now, thanks to a friend, I am ever closer to accepting that inflation may not be a problem for an even longer time than I expected. He sent me a link to an article called “The Fed won’t taper as long as inflation is low” (by Rex Nutting at MarketWatch) that makes the convincing case that not only is inflation low, but the Federal Reserve has so far seemed powerless to generate the inflation it wants. (I recognize the limitations of government data on inflation, but I do not subscribe to theories that they are concocted specifically to hide true inflation). Incredibly, core inflation is apparently at its lowest point since 1959 (the core PCE price index):

Rex Nutting uses this graph to make the point that all the Fed’s QE have failed to go reflate according to the Fed’s goals

Nutting also links to a paper from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York called “Drilling Down into Core Inflation: Goods versus Services.” In this paper, authors M. Henry Linder, Richard Peach, and Robert Rich demonstrate that more accurate inflation forecasts come from breaking out CPI into a services and a goods component. Nutting uses this as reference for the claim that the Fed is failing because of global disinflation. This global disinflation is responsible for a decline in the prices of the goods component. Services inflation is much more sensitive to domestic forces (we all know about skyrocketing healthcare and education costs). However, I am not sure where housing sits on this spectrum. It seems to provide a crossroad of forces given housing is not tradeable but foreigners are certainly free to overwhelm a housing market with cash. Foreign demand is reportedly helping to drive up housing prices in some of America’s hottest housing markets like in California and some parts of Florida.

All this to say that, for the moment, inflation is all but dead. But “Inflation Watch”, this blog, is NOT dead. I remain vigilant because I believe that when inflation DOES come, the Federal Reserve will either be ill-equipped to handle it and/or unwilling to snip it early for fear of causing a severe economic calamity. I am a gold investor, and I am eager for another chance to invest in the midst of a commodity crash (I am LONG overdue for an update to my framework for investing in commodity crashes/sell-offs).

The chart below from the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) shows that commodity prices remain at historically high levels, mostly thanks to rapacious demand from China. The current relative decline is what is helping to drive goods inflation down. The 2011 peak was well above the pre-crisis peak where prices have fallen now. Also note that prices are much more volatile. I suggest that this chart should remind us that commodity prices are a tinder box that can flare up at anytime. Aggressive rate-cutting by the RBA should also help keep prices aloft.

From the Australian perspective, commodity prices remain historically high although they have returned to their pre-crisis peak.

So stay tuned. Just when everyone finally concludes that the world has reached a golden age of disinflation where surpluses abound across the planet…that could be the exact moment the tide turns.

Be careful out there!

Full disclosure: long GLD

The Federal Reserve finally tries to fight a bubble…in the price of farmland

Posted: October 18, 2011 Filed under: Agriculture, Banks, Government | Tags: farmland, Federal Reserve, regulation Leave a comment(Hat tip to a friend who pointed me to this article)

Under Alan Greenspan, the Federal Reserve was known to stand on the sidelines while bubbles in asset prices grew and grew. Greenspan had a lot more faith in the Federal Reserve’s ability to mop up the subsequent mess caused by a bubble’s collapse than in its ability to stop a bubble, much less identify one.

It seems times have changed. On October 13, Businessweek chronicled the Fed’s efforts to make sure that soaring prices in agricultural land do not lead to another messy bubble and economic calamity. Prices have indeed soared across the midwestern United States:

“The Kansas City Fed reported land values were 20 percent higher than a year ago. The Chicago Fed reported a 17 percent increase in its district, the fastest increase since the 1970s. Nonirrigated farmland in the Minneapolis Fed district increased 22 percent in price.”

The factors driving these increases are the same as I reported from a related Planet Money piece: “Land prices have doubled in Iowa over the past few years“: “elevated crop prices, soaring farm income, and record-low interest rates.”

As a result, nervous regulators are demanding rigorous stress tests of banks up to their gills in agricultural loans. Businessweek also reports that regulators are “…scrutinizing the lending standards, loan documentation, and risk management at the country’s 2,144 agriculture banks.”

I will be very interested in the outcome of all this scrutiny. The same Federal Reserve that helped create record low interest rates is working to ameliorate the impact of those very same interest rates. This episode is a reminder that flooding an economy with liquidity does not produce equal outcomes for all sectors. Recovery and prosperity does not even need to appear in the sectors most impacted by the malaise the Federal Reserve scrambles to repair. Instead, the money tends to collect where it will generate the highest returns due to other economic factors. Currently, it seems that the bet is on farming. I believe the Federal Reserve was aiming for housing…

Bullard recommends targeting monetary policy at headline, not core, inflation

Posted: July 9, 2011 Filed under: CPI, Disguised inflation, Monetary Policy | Tags: chained consumer price index, Federal Reserve, headline inflation, James Bullard Leave a commentThe Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis just published an article written by James Bullard, a non-voting member of the Federal Reserve and President of the St. Louis Fed, called “Measuring Inflation: The Core Is Rotten.” It is based on a speech Bullard delivered two months ago to the Money Marketeers of New York University. It is a refreshing perspective on the use of core inflation for guiding monetary policy; it is also a bit surprising coming from someone on the Federal Reserve!

Bullard starts and ends with a critique familiar to those of us who insist food and energy prices should not be excluded from measures of inflation:

“One immediate benefit of dropping the emphasis on core inflation would be to reconnect the Federal Reserve with households and businesses who know price changes when they see them. With trips to the gas station and the grocery store being some of the most frequent shopping experiences for many Americans, it is hardly helpful for Fed credibility to appear to exclude all those prices from consideration in the formation of monetary policy…

…The headline measures of inflation were designed to be the best measures of inflation available. It is difficult to get around this fact with simple transformations of the price indexes. The Fed should respect the construction of the price indexes as they are and accept the policy problem it poses. To do otherwise may create the appearance of avoiding responsibility for inflation…”

(Compare and contrast this to Governor Frederic S. Mishkin’s insistence in 2007 that the Federal Reserve should care about headline inflation but focus on controlling core inflation in its public stance on monetary policy.)

I love the recognition that average consumers and businesspeople “know price changes when they see them.” This is Inflation Watch’s reporting philosophy and helps explain my emphasis on reporting the price changes of a broad range of products and services.

Bullard makes some key points to argue that headline inflation can and should be the focus of monetary policy. While I agree with his overall thesis, I do take issue with some of the points (my comments in bold):

- Monetary policy can be adjusted to accommodate the extra volatility in headline inflation by, for example, focusing on year-over-year changes.

- The relationship between core and headline inflation is unclear and even changes over time, making it more difficult to comprehend the optimal policy response. Me: This was an interesting point since the Federal Reserve’s statements usually imply the Federal Reserve tunes policy for core, not headline, inflation anyway. Currently, Ben Bernanke has all but absolved monetary policy of any impact on commodity prices.

- The Federal Reserve cannot directly influence supply and demand dynamics for any particular product in the inflation index, so it is not sufficient to ignore prices that are supposedly out of the Federal Reserve’s control. Me: I understand Bullard’s point, but I also think providing cheap money that traders can easily borrow to bid up the prices of goods and services is a strong and sufficient influence. The Federal Reserve definitely thinks it can directly influence housing demand and prices given its targeted efforts at lowering mortgage rates.

- When the price of one good goes up, another goes down as consumers adjust their demand to stay within their budgets. Increasing food and energy prices can thus force other prices down in the core index and further understate true inflation.

Bullard further notes that their is promising research into directing monetary policy at a specific subset of prices that households care most about, but it is too early to use.

Of particular interest to me was Bullard’s identification of a changing world where commodity prices will join the prices of medical care (and education) in outpacing the overall average inflation rate.

“…much of the contemporary worry about commodity prices is that relative price changes may be much more persistent going forward than they have been in the past…

…it is at least a reasonable hypothesis that global demand for energy will outstrip increased supply over the coming decades as the giant economies of Asia, particularly India and China, reach Western levels of real income per capita. If that scenario unfolds, then ignoring energy prices in a price index will systematically understate inflation for many years.”

(See “Preparing for Profits in a Resource-Constrained World” on implications for investing).

Given the limitations and blind spots of core inflation, Bullard makes a convincing case for directly targeting headline inflation with monetary policy. Otherwise, the Federal Reserve remains at risk for maintaining monetary policies that are too loose for too long.

The Federal Reserve May Choose to Ignore the Inflation Expectations of Households

Posted: June 4, 2011 Filed under: commodities, CPI, Monetary Policy | Tags: Federal Reserve, inflation expectations, inflation forecast Leave a comment(Originally appeared in “One-Twenty Two“)

First, Bernanke made it clear he thinks gold is not a good indicator of inflation expectations. Now, the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco has produced research that could convince the Fed to insulate itself from the inflation expectations of average Americans in “Household Inflation Expectations and the Price of Oil: It’s Déjà Vu All Over Again” by Bharat Trehan (thanks to Bill Fleckenstein for calling this article to my attention).

Household inflation expectations have risen to 4.5% from 3% at the end of 2010. Fortunately for the Federal Reserve, its empirical research seems to show that household expectations have become inaccurate and irrelevant for monetary policy:

“This Economic Letter argues that the jump in household inflation expectations is a reaction to the recent energy and food price shocks, following a pattern observed after the oil and commodity price shocks in 2008. The data reveal that households are unusually sensitive to changes in these prices and tend to respond by revising their inflation expectations by more than historical relationships warrant. Since commodity price shocks have occurred relatively often in recent years, this excessive sensitivity has meant that household inflation expectations have performed quite badly as forecasts of future inflation.”

Trehan admits that the University of Michigan’s Survey Research Center shows that households had been pretty good indicators of future inflation from the 1970s to 2000. However, over the past several years, the increased volatility in the prices of food and energy have misled consumers to anticipate more future inflation than is warranted given low levels of existing core inflation:

“The recent jump in the Thomson Reuters/University of Michigan measure of household inflation expectations appears to be related to increases in the prices of energy and food, similar to the jump observed in 2008. The size of this response to noncore inflation cannot be justified in terms of the historical relationships in the data. This disproportionate response is probably the reason why household inflation expectations have not done well as forecasts of future inflation in recent years, a period of volatile food and energy inflation. The poor forecasting performance argues against reacting strongly to the recent increases in household inflation expectations.”

Moreover, recent increases in inflation expectations are not justified by changes in monetary policy. Trehan speculates that…

“It’s also possible that households’ sensitivity to noncore inflation goes up following substantial, sharp increases in the price of energy and food items, such as those that occurred in the 1970s and over the past few years…This similarity to the 1970s is unsettling because it suggests that consumers are not accounting for the ways monetary policy has changed over this period.”

I assume this claim means that the Federal Reserve’s monetary policies have improved since the 1970s. In my opinion, we have seen even less reason to trust in the Federal Reserve’s policies to the extent that these policies “fix” economic problems in such a way to help set up the next crisis. These crises build while the Federal Reserve tends to reassure that it has everything under control and/or there is nothing happening to cause concern.

I would challenge the historical record and related regressions to suggest we need to consider whether the structural underpinnings of inflation are changing in ways that the Federal Reserve will be slow to recognize. Whether the Federal Reserve can do anything about these changes is another question.

A danger of inflation: The misallocation of resources on the way to sustained price increases (an explanation of the mission of Inflation Watch)

Posted: May 31, 2011 Filed under: CPI, Disguised inflation, energy, Monetary Policy | Tags: Bill Fleckenstein, Federal Reserve, inflation, inflation expectations, oil Leave a commentIn January of this year, Professor Russ Roberts of George Mason University invited fellow economics professor Don Boudreaux to address “Monetary Misunderstandings” on the weekly podcast “EconTalk.” From the synopsis:

“Don Boudreaux of George Mason University talks with EconTalk host Russ Roberts on some of the common misunderstandings people have about prices, money, inflation and deflation. They discuss what is harmful about inflation and deflation, the importance of expectations and the implications for interest rates and financial institutions.”

I was most interested in the discussion about the definition of inflation because I understand the importance of maintaining technical and economic clarity on this topic for “Inflation Watch.”

Boudreaux first deferred to Milton Friedman’s famous empirical proclamation “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon” and lamented that the economics profession no longer defines inflation as an increase in the money supply. Now, inflation represents a sustained increase in the average price level in the economy. Inflation is not simply any increase in price; Boudreaux complained that this definition is a common misconception of non-economists. However, he acknowledged that he personally thinks inflation’s largest threat is the process by which price increases become sustained. This process features uneven injections of money into the economy, causing specific and identifiable distortions in the economy that lead to a misallocation of resources. (Roberts somewhat disagreed as he expressed much greater fear of hyperinflation).

Bill Fleckenstein first taught me this notion that increases in the money supply distort specific areas of the economy. Such distortions can morph into bubbles, inflation’s ultimate misallocation of resource (capital). Bubbles can occur without ever tipping the economy into an inflationary cycle via official government statistics. So, it is very easy, for example, for the Federal Reserve to do nothing about soaring prices in an important sector of the economy and instead simply plan for the ultimate clean-up of the bubble’s aftermath. In recent history, the disastrous wakes of bubbles have forced the Federal Reserve to resort to easy money policies that invariably help fuel the next bubble. (Fleckenstein famously reviews this process and a lot more in “Greenspan’s Bubbles: The Age of Ignorance at the Federal Reserve.”)

Through Inflation Watch, I identify news of price increases not because any one price hike defines inflation; as noted above, this approach is technically incorrect. Instead, these stories offer clues that potentially can uncover the misallocations of capital that flag inflationary forces may be developing. I am trying to piece together a mosaic of economic activity that may provide early indicators of inflation well ahead of the moment that government statistics show it or the moment the Federal Reserve officially announces an inflationary process is underway.

The general context is important. We are currently experiencing an extended period of easy money policies in most of the globe’s developed economies. Presumably, this money must go “somewhere” at some point in time. Financial markets are the perfect conduit for easy money; investors and speculators alike will flock to those parts of the economy that promise some protection against the devaluation of currency and/or profits from inflationary pressures. (Boudreax and Roberts never directly addressed the enabling influence of financial markets for transmitting inflationary pressures). I have argued in previous posts that the most favorable hosts for easy money are where demand is particularly robust and supply may be constrained or stressed. Today, commodities represent a perfect storm for global easy money policies. So, many of the recent stories in Inflation Watch have focused on commodities and industries dependent on consuming commodities.

The Federal Reserve’s current bias toward inflation shows because the Fed has demonstrated relatively quick action to thwart the perceived threat of deflation. The specter of the Great Depression always looms large. Recall that after the dot-com bubble burst, Greenspan cited the threat of deflation as a prime reason for aggressively loosening monetary policy. The crash of the housing bubble of course generated an even more aggressive policy of monetary easing given housing’s importance to the overall economy and consumer spending. The Federal Reserve’s recent success in averting deflation certainly adds confidence in applying easy money policies, much to the likely chagrin of devout deflationists. Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve has also made it clear that it will not act against inflation until price increases (or the expectation of price increases) reach sustained levels over time.

For example, last week, Bloomberg quoted Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago President Charles Evans in “Fed’s Evans Says ‘Slow Progress’ in Economy Justifies Maintaining Stimulus“:

“Inflation is a continuing increase in the price level over time: A one-off increase in the price level is not inflation…Price increases have to be sustained.”

I duly noted that at no time does someone from the Federal Reserve insist that deflation is a continuing decrease in the price level over time!

Evans goes on to express his comfort with the current levels of inflation by citing empirical research showing no correlation between higher oil prices and inflation. Even a casual examination of the current record of price increases demonstrates that oil’s price rise is just one small part of the general increase in prices percolating in the economy, especially where demand is strong and supply is compromised. Regardless, the conclusion of this research is intuitive given the numerous supply-related fluctuations in oil that have occurred with and without Fed monetary action. As we saw above, it is not likely that the increase in prices in any one part of the economy will produce the sustained increase in price levels required to signal inflation’s arrival. Without an increase in the money supply, increases in oil prices steal money from some other products in the consumer’s basket of goods. The net impact on official inflation statistics may be close to zero and “core” inflation, subtracting energy and food, could even decrease! But if increases in the money supply happen to coincide with a strengthening oil market, I contend we better look out.

The bias of the Federal Reserve toward inflation is also rooted in the concept that “a little inflation” is good for the economy because it encourages spending. Specifically, inflation encourages consumers to buy today to avoid paying higher costs tomorrow. In a deflationary environment, consumers just wait and wait and wait. Boudreaux and Roberts sharply criticize this theory and cite examples demonstrating the fallacy of such thinking. For example, with even a little inflation, why don’t sellers just wait until tomorrow to sell since they can make higher profits? Why do consumers buy computers and many other electronic goods knowing full well that prices will be lower tomorrow (not to mention these goods will be of higher quality)? Why was America’s post-Civil War economy so strong for almost 30 years despite persistent deflation? Clearly, buyers and sellers are motivated not just by relative prices, but also the relative value (or utility) gained from consumption and/or alternative investments.

I have covered the core concepts reviewed by Boudreaux and Roberts related to the philosophy and approach of “Inflation Watch.” If you want more detail, I highly recommend listening to the podcast, reviewing the transcript, and/or perusing some of the references provided by EconTalk. Hopefully, you have also gained a better understanding of Inflation Watch’s mission: “Watching for inflation here, there and everywhere.”

Housing prices hit new lows

Posted: May 5, 2011 Filed under: Housing, Monetary Policy | Tags: deflation, Federal Reserve, foreclosures, Monetary Policy, mortgage 1 CommentCNBC reported on a study from Clear Capital titled “Clear Capital Reports national Double Dip“:

“Home prices have double dipped nationwide, now lower than their March 2009 trough…a surge in sales of foreclosed properties and a big push by banks to facilitate short sales…[forced] home prices down dramatically. Sales of bank-owned (REO) properties hit 34.5 percent of the market, according to the survey, resulting in a national price drop of 4.9 percent quarterly and 5 percent year-over-year. National home prices have fallen 11.5 percent in the past nine months, a rate not seen since 2008.”

CNBC goes on to indicate that the foreclosure problem has spread beyond just the “bubble” markets that were at the center of the housing crisis:

“…the mid-west is seeing a surge in REOs now, thanks to the plain old recession. 40 percent of the Chicago market is foreclosures, 43 percent in Cleveland and 51 percent in Minneapolis. Home prices fell 8.7 percent in the Mid-West during the past three months compared to the previous quarter.”

For more see CNBC’s article: “National Home Prices Double Dip” (or read the report).

It is once again important to note that housing was one of the big targets of the Federal Reserve’s dollar-printing campaign. Given that housing prices have not responded while commodity prices have soared, we must now wonder whether the Fed believes it simply did not print enough, whether there is a longer time lag than anticipated to seeing an impact in housing, and/or worry about the unintended consequences that have yet to be seen. The money had to go somewhere; so far, it has not been into housing.

Can the Oil and Gas Price Fraud Working Group Succeed Without Examining Monetary Policy?

Posted: April 24, 2011 Filed under: energy, Monetary Policy, oil | Tags: Federal Reserve, fraud, gas prices, Monetary Policy, oil Leave a commentTime for some comedic relief. On my main site “One-Twenty Two” I posted my own satirical commentary on the recent announcement from Attorney General Eric Holder about the formation of the Oil and Gas Fraud Working Group. This taskforce is supposed to ensure prices properly reflect “real” supply and demand factors from the marketplace. In my post, I ponder what the story would look like if Holder decided to go after the Federal Reserve’s role in generating higher oil and gas prices (mainly through killing the U.S. dollar). Click here to read it.

Fleckenstein declares deflation “dead”

Posted: April 14, 2011 Filed under: commodities, Disguised inflation, Monetary Policy | Tags: Bill Fleckenstein, Federal Reserve, inflation expectations Leave a commentI am two months late on this one.

In February, Bill Fleckenstein refuted the notion that inflation is a net positive in “No such thing as good inflation.” He starts by noting how higher prices in commodities are driving inflation expectations upward:

“As unprecedented amounts of liquidity from the Federal Reserve have worked their way through the financial system and into the real world, I believe inflation psychology has changed. People have seen larger price increases in commodities and are resigned to accept them, which will set the stage for additional rounds of price hikes.

Once that psychological shift becomes entrenched, it will be extremely hard to reverse, despite Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke’s stated certainty that he can keep prices under control…”

Fleckenstein goes on to insist that as long as the Federal Reserve is allowed to play free and loose with the dollar, deflation will not happen in America:

“I would like to officially declare the topic of deflation dead. As I have long maintained, we may actually experience deflation if the bond market rebels and takes the printing press away from the Fed. However, in the absence of that, it should be clear by now that deflation is not going to visit the shores of America.”

I made a related point back in October, 2008. Back then I thought we would see elevated inflation levels no later than 2010. Regardless, Fleckenstein provides to a great reminder that inflation is, and has always been, the threat once the Federal Reserve started throwing freshly printed bills at our economic calamities.

The Federal Reserve debates inflation

Posted: April 6, 2011 Filed under: Monetary Policy | Tags: Federal Reserve, inflation expectations, Monetary Policy 1 CommentWith so much heated debate and discussion about inflation in the media these days, I thought I would focus on how the Federal Reserve discussed and debated inflation in the latest meeting minutes released today.

The Federal Reserve’s staff economists concluded that while commodity prices have increased substantially and near-term inflationary expectations have also increased, the outlook for medium and long-term inflation remained stable. In other words, current inflationary pressures should prove “transitory.”

“Sizable increases in prices of crude oil and other commodities pushed up headline inflation, but measures of underlying inflation were subdued and longer-run inflation expectations remained stable…

…According to the Thomson Reuters/University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers, households’ near-term inflation expectations increased substantially in early March, likely because of the run-up in gasoline prices; longer-term inflation expectations moved up somewhat in the early March survey but were still within the range that prevailed over the preceding few years.

…Measures of inflation compensation over the next 5 years rose, on net, over the intermeeting period, with most of the increase concentrated at the front end of the curve, likely reflecting the jump in oil prices. In contrast, measures of forward inflation compensation 5 to 10 years ahead were little changed, suggesting that longer-term inflation expectations remained stable.

…The staff revised up its projection for consumer price inflation in the near term, largely because of the recent increases in the prices of energy and food. However, in light of the projected persistence of slack in labor and product markets and the anticipated stability in long-term inflation expectations, the increase in inflation was expected to be mostly transitory if oil and other commodity prices did not rise significantly further. As a result, the forecast for consumer price inflation over the medium run was little changed relative to that prepared for the January meeting.”

Some Federal Reserve members expressed their concern that current inflationary pressures may still lead to upward pressure on long-term expectations:

“…participants observed that rapidly rising commodity prices posed upside risks to the stability of longer-term inflation expectations, and thus to the outlook for inflation, even as they posed downside risks to the outlook for growth in consumer spending and business investment.”

InflationWatch has chronicled numerous instances of companies that either plan to or already have passed on price hikes to consumers. The Federal Reserve is also noticing, but their “contacts” are apparently not confident that plans for price hikes can stick:

“A number of business contacts indicated that they were passing on at least a portion of these higher costs to their customers or that they planned to try to do so later this year; however, contacts were uncertain about the extent to which they could raise prices, given current market conditions and the cautious attitudes toward spending still held by households and businesses.”

I often whether in these circumstances whether the Federal Reserve passes on some “friendly” advise to these contacts…

The most common reason cited for assuming inflation will remain tame is that there remains a large amount of slack in resource utilization in the economy. Someone on the Fed recalled an important exception to such assumptions:

“Some participants pointed to research indicating that measures of slack were useful in predicting inflation. Others argued that, historically, such measures were only modestly helpful in explaining large movements in inflation; one noted the 2003-04 episode in which core inflation rose rapidly over a few quarters even though there appeared to be substantial resource slack.”

One way to keep inflation expectations anchored is to insist that it will stay anchored. Ben Bernanke has planned to do press conferences, and the rulebook assurances over inflation may be part of the motivation:

“A few participants noted that the adoption by the Committee of an explicit numerical inflation objective could help keep longer-term inflation expectations well anchored.”

Finally, the topic of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet came up. I have long maintained that the Fed will find itself unable to wind down this balance sheet quickly or in a timely fashion. Some on the Fed are afraid that more people like myself will harbor these same doubts:

“…a few participants noted that if the large size of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet were to lead the public to doubt the Committee’s ability to withdraw monetary accommodation when appropriate, the result could be upward pressure on inflation expectations and so on actual inflation. To mitigate such risks, participants agreed that the Committee would continue its planning for the eventual exit from the current, exceptionally accommodative stance of monetary policy.”

This path toward an exit is likely fraught with monetary perils and should provide a lot more volatility in financial markets. Stay tuned.

Evans not worried about inflation because of high unemployment

Posted: March 29, 2011 Filed under: Jobs, Monetary Policy | Tags: Charles Evans, Federal Reserve, unemployment Leave a commentCharles Evans, President of the Chicago Federal Reserve, recently spoke at The Darla Moore School of Business giving “A Perspective on the Current Economy.” The press summarized the lecture by indicating Evans remains a “dove” on inflation:

“The Fed is more sanguine about inflation than some because an outbreak of higher prices is missing a key ingredient – higher wages, Evans said…A weak labor market will continue to exert important downward influences on inflationary pressures, he said.” (from Marketwatch)

A cynical person could say that Evans does not fear inflation because QE2 has failed to provide the one single thing that Americans care most about in the economy right now: jobs. Instead, I will note that this commentary comes immediately on the heels of an op-ed piece from Laurence H. Meyer, a former governor of the Federal Reserve, who opined that inflation is not a problem…and even if it became one, the Fed would quickly get it back under control. Since the Federal Reserve cares more about inflation expectations than current levels of inflation, it makes a lot of sense that a good amount of energy is spent trying to convince people that no matter what the data say or the anecdotal evidence (or Inflation Watch postings for that matter!), the future is fine.

However, the Wall Street Journal noted that the commentary from Evans runs directly counter to the warnings of coming inflationary pressures from FOMC voting member Charles Plosser, president of the Philadelphia Federal Reserve Bank (see here). Apparently, the gameplan and script are not receiving the same reading on the team!

Laurence Meyer confident in Fed’s ability to respond to an increase in inflation expectations

Posted: March 28, 2011 Filed under: CPI, Monetary Policy | Tags: Federal Reserve, inflation expectations, inflation rate Leave a commentLaurence H. Meyer, a former governor of the Federal Reserve, wrote an op-ed in the New York Times titled “Inflated Worries” in which he confidently argues that inflation expectations remain well-contained and even if they became unhinged, the Federal Reserve is ready to respond quickly:

“The Fed, this argument goes, just won’t be able to act quickly enough to turn off the spigot when the time comes to do so.

But the Fed can raise interest rates directly any time it wants. In addition, it could start to sell the huge volume of Treasury securities and other financial assets on its books, which would also place upward pressure on rates.

Would the Fed act in time? I expect that it will. And even if it doesn’t act in time, and inflation expectations start to get out of line, I am confident that the Fed would tighten monetary policy quickly and aggressively enough to restore price stability and maintain its credibility on inflation. You can take that to the bank.”

Meyer’s unspoken assumption in this piece is that unemployment would not be so high that it discourages the Federal Reserve from acting. Ben Bernanke has made it abundantly clear that unemployment is front and center and that the growing concerns about inflation around the globe are not his or America’s concern. So, I remain extremely doubtful that the Federal Reserve is unconditionally prepared to act in the face of rising inflation expectations.

Meyer also explains in his piece the difference between core and non-core (or headline inflation). He disabuses the audience of the notion that higher food and energy prices increase inflation expectations citing Federal Reserve research that “…unequivocally tell us that core inflation better predicts overall inflation tomorrow” (see “Estimating the common trend rate of inflation for consumer prices and consumer prices excluding food and energy prices“). However, Meyer blithely ignores the study’s conclusion that this relationship did NOT hold during the 1970s and 1980s: “In the 1970s and early 1980s, movements in overall prices and prices excluding food and energy prices both contained information about the trend.” In other words, there is little in this study to suggest that the relationships are stable.

Ultimately, I think those who argue that there are fundamental, structural pressures that indicate increasing energy and food prices are reflective of inflation’s future direction, especially once supply constraints finally show up in more sectors of the economy, will prove to be the most prepared for the future. In other words, today’s food and energy inflation has been an early outcome of easy money policies because supply constraints and demand dynamics are most readily exploited in these sectors of the global economy right now. (I made a related argument when discussing the recent rapid increase in coffee prices).

Hopefully through inflation watch you have been able to note the growing pockets of inflation pressure and the increasing power companies have to raise prices at least at the producer level…

Dudley remains focused on the U.S. output gap

Posted: March 1, 2011 Filed under: Economy, Monetary Policy | Tags: Federal Reserve, output gap Leave a commentGavyn Davies at the Financial Times writes a good review and critique of William Dudley’s recent speech at New York University’s Stern School of Business, New York City titled “Prospects for the Economy and Monetary Policy.”

Davies notes that Dudley, President and Chief Executive Officer of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, remains laser focused on the output gap and unemployment in the U.S. and relies on them to provide a buffer of comfort versus inflation. Dudley is not worried about other signals of inflationary pressures, like rising commodity prices driven by demand, as long as inflation expectations remain contained. We have shown numerous examples in these pages of how these expectations are actually tilting toward inflation. It remains unclear when the Federal Reserve will also notice.

For more details see “The Fed doves have not caved in.”

Fidelity notes stocks are benefiting from an inflationary boom

Posted: February 24, 2011 Filed under: Bond market, commodities, energy, food, Monetary Policy | Tags: Federal Reserve, Monetary Policy, quantitative easing Leave a commentGreat piece from Fidelity considering the implications of the inflationary boom that seems to be driving stocks skyward (“Is this bull unstoppable? The key is how—and when—the Fed exits its historic stimulus program.”)

I highly recommend reading the article as it contains excellent charts showing the relationships amongst monetary policy, earnings, stock prices, and commodity prices.

Here are some key quotes:

“I believe it is becoming increasingly clear that stocks are following the playbook of an inflationary boom. The Institute for Supply Management’s (ISM) January 2011 manufacturing survey is the highest in years, earnings are strong, and now money supply growth is picking up steam. Ultimately, I fear this inflationary boom scenario may be followed by an inflationary bust (or stagflation), but perhaps that day is farther away than I have been anticipating.”

“Food and energy prices have moved sharply higher in recent months and appear to be trending higher rather than mean-reverting. If this remains the case, I believe the Fed could misstep by focusing on core inflation rather than the perhaps more relevant headline inflation. After all, for most of the world, food and energy inflation are critical matters.”

“How long can this go on before the “rubber band snaps,” either by commodities plunging in a deflationary crash (like in 2008) or the Fed being forced (by the bond market) to tighten and thereby undermine the recovery? Or what if the Fed does nothing and the dollar falls further and sends inflationary expectations skyward?”

![Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: New Vehicles in U.S. City Average [CUSR0000SETA01], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, March 21, 2022.](https://inflationwatch.files.wordpress.com/2022/03/fredgraph.png?w=1024)